Dante Alighieri

The poetical works of the fourteenth century Florentine poet, Dante Alighieri, have influenced western artistic tradition for the last seven hundred years. From Botticelli to William Blake, Chaucer to Milton, Franz Liszt to Sepultura, the shadow cast by Dante is as profound as it is long. Few other artists can claim to have ingrained themselves so deeply into our modern world, even if we don't always fully appreciate it.

In considering the influence of Dante's work, a multitude of paths are open for the critic to take. In this essay I am going consider the numerological and geometric aspects of Dante's poetry. I will then turn to look at how these aspects came to influence two novels in particular: Moby Dick by Herman Melville and Finnegans Wake by James Joyce. In doing so, further examination of Dante's influences will be considered. Finally, I will examine some of the ways in which Moby Dick influences Finnegans Wake, before turning full circle back to Dante and the totality of his influence.

Dante's most famous and influential composition is The Divine Comedy. Told over one hundred verses, or Cantos, The Divine Comedy depicts Dante's journey through the three realms of the Christian afterlife. Waking in a dark wood, Dante the Pilgrim (as distinct from Dante the Poet) finds himself beset on all sides by beasts of prey: leopard, lion and she-wolf. He is rescued by the Roman poet, Virgil, who leads Dante down through the nine circles of Hell and up past nine levels of the island of Purgatory. Dante is then reunited with the Florentine woman, Beatrice, who escorts him through Paradise, across nine heavenly spheres. Finally he arrives at the Empyrean, a celestial rose sitting at the centre of the nine spheres, where the Holy Trinity of father, son and holy ghost reside.

Threes and nines appear time and again within the structure of The Divine Comedy. Groups of three reflect the perfection of the holy trinity. At the centre of the Inferno we find Satan, trapped, 'stuck out with half his chest above the ice'. His head contains three faces, each mouth chewing upon one of three traitors to their Lord: Judas Iscariot, who betrayed Jesus Christ to the Romans, and Brutus and Cassius, main conspirators against Julius Caesar.

As with much of The Divine Comedy, the severity of punishment here is highly subjective. The choice of Judas is obvious, yet to make both Brutus and Cassius share his fate serves almost to diminish Iscariot's treachery. Was the betrayal and murder of Caesar twice as egregious as that inflicted upon Christ? As more than one commentator has made plain, Jesus was required to die for the sins of man. Without his death, the path to Paradise would remain closed. Judas then can be seen as more patsy than villain.

Satan's three-fold faces act as mockeries of the trinity, as do the three beasts that Dante encounters in the first Canto. The leopard, lion and she-wolf are metaphors for the three types of sin punished in the Inferno, those of incontinence (originally meaning indiscipline), violence and fraud. The three beasts are counterbalanced by a further trinity, the Three Graces, the make-up of which Virgil explains to Dante in the second Canto of the poem.

As Dante finds himself in trouble, the Virgin Mary espies his plight from upon high in heaven and tells Saint Lucia, 'the enemy of cruelty', to send out Beatrice. Beatrice then travels down to Limbo, the first circle of Hell, where virtuous pagans are kept. She commands Virgil to rescue Dante, then returns to her seat in high heaven.

If God is represented by the number three, then the perfection of his creation is represented by the number nine. For Dante, the personification of this perfection was encapsulated by Beatrice. As he explains in his other great masterpiece, Vita Nuova:

The number three is the root of nine, because, independent of any other number, multiplied by itself alone, it makes nine, as we plainly see when we say three threes are nine; therefore if three is the sole factor of nine, and the sole factor of miracles is three, that is Father, Son and Holy Ghost, who are three and one, then this lady was accompanied by the number nine to convey that she was nine...

The Vita Nuova is a series of poems and commentaries, most of which were written with reference to Beatrice. It is not know for certain who Beatrice was, but most commentators accept that she was the daughter of a prominent Florentine citizen, Folco dei Portinari. Dante first met her when he was nine years old, she eight, and, if we are to believe the content of Vita Nuova, he fell immediately in love with her. However, this was a courtly love, never consummated, Beatrice marrying an influential banker in the town, before dying at the tender age of twenty four. The commentaries of Vita Nuova were written a few years after her death, perhaps as a way for Dante to cope with his grief, although the actual poetry was composed during her life and helped to make Dante the most famous poet in Florence at that time.

How much of what Dante tells us is true and how much is that of a star crossed lover making the facts fit his thesis it is impossible to say, but Dante recounts how many times the number of nine figured in his experiences of Beatrice. He meets her for the second time at eighteen, nine years after their first encounter. Then a vision of Love appears to him at the foot of his bed, commanding him to write verses to her, which he claims to have happened during the ninth hour of the day. And of her death, Dante states:

[A]ccording to the Arabian way of reckoning time, her most noble soul departed from us in the ninth hour of the ninth month of the year...

Being October in the Christian calendar. Beatrice died in 1290, in which Dante again finds great significance.

The Christian vision of the universe at that time was taken from the Ptolemaic view that the Earth stayed immobile and the sky rotated around it upon nine heavenly spheres. Each of the five known planets ('planetai' - wandering stars) occupied a single sphere, as did the Sun and Moon. The eighth sphere contained all of the fixed stars, including the Milky Way, and the ninth was called The Prime Mover. The Prime Mover was a theoretical sphere that had originally set the universe in motion. The number nine then truly represents perfection and for Dante Beatrice was the epitome of the genius and glory of God.

Dante concludes his Vita Nuova by stating that if God will 'continue my life for a few years, I hope to compose concerning her what has never been written in rhyme of any woman'. This desire became The Divine Comedy.

Mathematically, nine works so well because the sum of the individual digits of any multiple of nine also equals nine. The Divine Comedy is split into three parts, called Canticles. There are nine circles to the inferno, nine levels to purgatory and nine heavenly spheres. Three nines are twenty seven, two and seven equal nine. Moreover, if the opening Canto of The Divine Comedy serves as a prologue (and a microcosm of the entire work), then its three Canticles (The Inferno, Purgatory and Paradise) are each thirty three verses long. Three times three is nine. Also, three raised to the power three (three cubed) is twenty seven, which is nine. We can even multiply twenty seven by three again and get eighty one, which again has digits equalling nine.

However, Dante plays a further mathematical trick in The Divine Comedy. To each of these nines he adds an extra one, to make the numbers add up to ten, signifying the ultimate perfection of God. So, outside of hell proper, before Charon and his ferryboat across the river Acheron, we find the Vestibule. Here undecided souls, who have been neither virtuous nor sinful, are left to roam. At the summit of the island of Purgatory, with its nine levels, is the Garden of Eden, where Virgil hands Dante over to the care of Beatrice (as a pagan, Virgil may not enter heaven, even as a visitor). Finally, at the top of the nine heavenly spheres is the Empyrean, seat to the throne of God.

We can also see that three books of thirty three verses, plus the prologue of the first verse, equal the one hundred Cantos of The Divine Comedy, which again combine to express the magnificence of the one, true Christian deity. Each Canto is also broken down into a series of three line sections of verse, called tercets, with each Canto ending on a single line of verse.

We can also see that three books of thirty three verses, plus the prologue of the first verse, equal the one hundred Cantos of The Divine Comedy, which again combine to express the magnificence of the one, true Christian deity. Each Canto is also broken down into a series of three line sections of verse, called tercets, with each Canto ending on a single line of verse.It should also be noted that Dante sets The Divine Comedy in the year 1300, 'Midway along the journey of our life', which is to say when he was thirty five years old ('The days of our years are threescore years and ten' - Psalms 90). One hundred Cantos, plus thirty five years of age give us a figure of one hundred and thirty five. One, plus three, plus five equal nine.

Moby Dick, published by Herman Melville in 1851, contains one hundred and thirty five numbered chapters exactly. This hardly seems a coincidence, especially when you scratch the surface of Moby Dick even a little. Then you find threes and nines are also littered throughout its structure.

As well as a hundred and thirty five numbered chapters, Moby Dick also contains three ancillary chapters, the Epilogue, Etymology and Extracts. We can see that again where one, plus three, plus five equal nine, then nine times three unnumbered chapters gives us twenty seven, which is nine.

Moby Dick begins with three words, perhaps the most famous opening line in literary history. 'Call me Ishmael'. Despite the novel taking its name from the infamous whale which took Ahab's leg, Moby Dick does not appear in the book until three chapters from the book's conclusion. These final chapters are named, The Chase - First Day, The Chase - Second Day and The Chase - Third Day. Moby Dick begins with three, ends with three, and even its epilogue opens on three words, 'The drama's done'.

If we equate Ishmael with Dante, then Ishmael finds his Virgil in Queequeg. The novel opens on the island of Manhattan, from where Ishmael travels to the port of New Bedford, meaning to take a packet ship on to the island of Nantucket . Nantucket was a famous whaling port, where the first whale was said to have been captured by European Americans, stranded on the beach there. However, Ishmael misses his ship and finds he has to spend a night and a day in New Bedford and tramps around the town, looking for a suitable place to stay. Eventually, he settles on a tavern called 'The Spouter-Inn'.

If we equate Ishmael with Dante, then Ishmael finds his Virgil in Queequeg. The novel opens on the island of Manhattan, from where Ishmael travels to the port of New Bedford, meaning to take a packet ship on to the island of Nantucket . Nantucket was a famous whaling port, where the first whale was said to have been captured by European Americans, stranded on the beach there. However, Ishmael misses his ship and finds he has to spend a night and a day in New Bedford and tramps around the town, looking for a suitable place to stay. Eventually, he settles on a tavern called 'The Spouter-Inn'.The name of this tavern is also the title of the third chapter of Moby Dick and, like the first Canto of The Divine Comedy, can be seen as a microcosm of the whole. Here, Queequeg serves as substitute for the white whale, whose presence is often alluded to within the chapter, but only makes his appearance near the chapter's end.

In the opening Canto of The Divine Comedy, Dante tries to escape by climbing a hill, but his upwards movement is arrested by the three beasts. Before he can begin his journey upwards towards redemption, he has to travel down through the sins of hell. As Dante can only gain entrance to hell with the assistance of the pagan poet Virgil, so only through the pagan Queequeg's assistance can Ishmael finally reach Nantucket and that ill fated ship, the Pequod.

Within the hundred and thirty five named chapters, reference is made to nine ships by name:

The Pequod

The Albatross (Goney)

The Town-Ho

The Jeroboam

The Virgin (The Jungfrau)

The Rose-Bud (Bouton de Rose)

The Bachelor

The Rachel

The Delight

Aside from the Pequod, the eight remaining ships can be grouped into three sets, by how they are referenced in the chapter headings. The chapter concerning the ship Goney is simply called The Albatross. Later, we have chapters called, The Town-Ho's Story and The Jeroboam's Story. The remaining five ships are then referenced in titles which take the form, The Pequod Meets (The Pequod Meets the Virgin, etc.). This final group is most interesting, as they all seem to make reference to The Divine Comedy. The name of the Jungfrau or Virgin should be obvious, with its reference to the Virgin Mary, as should the Rose-Bud, with its allusion to the shape of the Empyrean, with the elect arranged around its petals and the trinity at the centre (the bud).

The Bachelor I am uncertain about, although it may simply continue the theme of purity and untouched innocence. It could also be a direct reference to Dante himself (from what little we know of Dante's life, he seemed to have lived something of a bachelor's life). In Canto twenty four of Paradise, Dante says:

Just as a bachelor arms his mind with thought

in silence till his master sets the question

to be discussed but not decided on,

so did I arm myself with arguments

while she was speaking, that I be prepared

for such a questioner and such a creed.

Which is a pretty good description of Ishmael, of whom we know very little. Ishmael keeps almost entirely silent about himself, but his mind is as full with thoughts and questions as a well stocked armoury.

Rachel, sister of Leah in the Old Testament, sits next to Beatrice in the Dantean order of high heaven. Finally, the name of the Delight may have a double meaning. It could have a direct concordance with Beatrice ('she who blesses' - 'she who brings delight'). However, delight can also be broken into de light, or of light, a reference to Saint Lucia, whose name literally means light. Given that Melville presents us with the English translations of ships with foreign names (Goney, Jungfrau and Bouton de Rose), it is not unreasonable to suppose that he is reversing the process in naming the final ship in the sequence.

The Pequod itself is first referred to in chapter sixteen, simply titled, The Ship. Whereas Ishmael has been led to believe that he and Queequeg will try to locate a ship together to sail aboard, Queequeg tells him that his god, Yojo, has already chosen the ship, which Ishmael should, 'light infallibly upon, for all the world as though it had turned out by chance'.

Ishmael sets out next morning, leaving Queequeg engaged in some kind of fasting ritual, of which Ishmael can make little sense. Enquires are made and he discovers that there are three ships offering three year voyages (three times three), all of which are berthed next to each other: The Devil-Dam, the Tit-Bit and the Pequod. Ishmael takes a look at each boat in turn, repeating the trinity of names three times before settling on the Pequod. Three times three make nine.

The previous evening, Queequeg tells Ishmael that Yojo had 'told him two or three times over' that Ishmael was to search for a ship on his own, foreshadowing the book's final end. Ishmael hops over from the Devil-Dam to the Tit-Bit, then over the Pequod. He will go over for a third time, over the Pequod's side and into the sea, when Moby Dick rips the ship apart.

The Pequod, as Ishmael reminds us, 'was the name of a celebrated tribe of Massachusetts Indians, now as extinct as the Medes'. The historian Howard Zinn, in his book, A People's History of the United States, presents a less euphemistic picture of the events of 1636:

The English developed a tactic of warfare used earlier by Cortes and later, in the twentieth century, even more systematically: deliberate attacks on noncombatants for the purpose of terrorizing the enemy.

Captain John Mason waited for the men to go out hunting, 'which would have over taxed his unseasoned, unreliable troops'. Then he ordered his men to attack the village, setting fire to wigwams full of women, children and the old and infirmed, running any and all survivors through with the sword:

As Dr. Cotton Mather, Puritan theologian, put it: "It was supposed that no less than 600 Pequot souls were brought down to hell that day."

The name of Ahab's ship then is well chosen, given the book's associations with Dante and his Inferno. Indeed, Moby Dick is as allegorical a work of fiction as The Divine Comedy. The Pequod, with its ragtag, mongrel crew of foreigners, heathens, dispossessed natives and its disabled captain, are hunting a common enemy. Moby Dick is very specifically a white whale. This is Herman Melville's symbolist outcry at the Indian massacres, as well as the American slave trade, written as it was a decade before the outbreak of the American Civil War that would finally bring slavery to an end.

The name of Ahab's ship then is well chosen, given the book's associations with Dante and his Inferno. Indeed, Moby Dick is as allegorical a work of fiction as The Divine Comedy. The Pequod, with its ragtag, mongrel crew of foreigners, heathens, dispossessed natives and its disabled captain, are hunting a common enemy. Moby Dick is very specifically a white whale. This is Herman Melville's symbolist outcry at the Indian massacres, as well as the American slave trade, written as it was a decade before the outbreak of the American Civil War that would finally bring slavery to an end.The novel was also composed around the time of the Mexican-American War (1846-1848), which resulted in Mexico losing a third of its territory to the United States. War was waged because many in the United States believed it was the country's God-given right to consume the entire continent of North America. This belief was encapsulated in the phrase, 'Manifest Destiny'. James Polk, President at the time of the Mexican-American War, was a firm believer in 'Manifest Destiny'. It hardly then seems a coincidence how close white whale sounds to White House. The American Civil War would see the death of US North-South expansion and consolidation of its territories to the west would become the new focus.

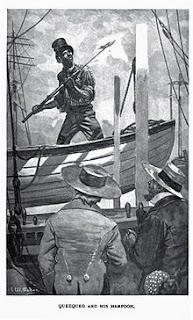

Melville's concerns surrounding slavery and the treatment of the indigenous population are reflected in the trinity of harpooners aboard the Pequod. Queequeg is the son of a Polynesian king, who desired to see Christendom and impelled an American ship to take him aboard when it returned to the Americas.

Melville's concerns surrounding slavery and the treatment of the indigenous population are reflected in the trinity of harpooners aboard the Pequod. Queequeg is the son of a Polynesian king, who desired to see Christendom and impelled an American ship to take him aboard when it returned to the Americas. 'Next was Tashtego, an unmixed Indian from Gay Head, the most westerly promontory of Martha's Vineyard'. Like Daggoo, 'a gigantic, coal-black negro-savage', from Africa, both are described by Ishmael as possessing the bearing, stature and nobility of princes. Each harpooner serves as squire to one of the Pequod's three mates. Queequeg to Starbuck, Tashtego to Stubb, Daggoo to Flask. In the only two titles which bear exactly the same name, Melville names two successive chapters, Knights and Squires, dedicated to the three mates and their respective harpooners. Yet the mates seem slight and inconsequential when placed next to their pagan subordinates, as Dante's three graces set against the leopard, lion and she-wolf.

The ultimate trinity though, like the white whale, lies beneath the surface. It is a trinity which speaks to obsession. At its head is Ahab. Ahab's obsession to find the beast that stole his leg, an obsession which fills him with such rage, to the inclusion of all else, even the life of his own crew, has been so well explored over the last century and a half that it barely requires expanding upon at this juncture.

Ahab, however, is not the only obsessive aboard the Pequod. What of Ishmael? As with Finnegans Wake, the narrative of Moby Dick owes much of its style to Lawrence Sterne's novel, The Life and Opinions of Tristam Shandy. Published in nine volumes during the 1760s, Sterne's masterwork is a shaggy dog story, a cock and bull story, a novel about the writing of a novel, which constantly veers off track and into a thousand and one digressions.

As Tristam Shandy is a cock and bull story, so Moby Dick is the greatest fisherman's tale ever told ('It was this big'). The actual plot of Moby Dick accounts for less than a third (maybe as little as a quarter) of the book's actual length. The rest of the novel is a continual digression away from the narrative, which takes into account every aspect of whales, whaling and the whaling tradition. Whole chapters are dedicated to the scientific classification of whales, whales in paintings, whale skeletons, fossilised whales, contrasted views of the head of the Sperm and Right Whale, Jonah as history, ambergris and scrimshaw art, to name but a few of its expansive subjects. Ishmael's own obsession in recounting every aspect of this business called whaling is as offspring to Ahab's pointed mania at capturing Moby Dick. The books real themes lay beneath the surface and its continual digressions are a way to avoid talking about what's really going on.

Now, it is a curious fact that the narrator of arguably America's greatest novel bears the same name as the forefather of the twelve tribes of Islam. In Islamic tradition it was Ishmael, not Isaac, that God commanded Abraham (Ibrahim) offer up in sacrifice, only to stay his hand at the last minute. In the Bible, Ishmael and his mother, the handmaiden Hagar, are banished to the wilderness when Isaac is born to Abraham and wife, Sara, and she becomes jealous of her son's rival. Of Ishmael, God tells Abraham, 'I will make him a great nation'.

Islam is very much part of American maritime tradition. While merchant ships had been sailing from American harbours since before the War of Independence, it was only in 1797, fourteen years after the war ended, that the first Naval ship, the United States, was launched. The formation of an American navy was in reaction to increasing piracy against U.S. merchant ships by Barbary Corsairs in and around the coast of North Africa. When the Pasha of Tripoli declared war on the United States in 1801, demanding tribute, it proved the final straw and American ships besieged Tripoli Harbour in a demonstration of brute force. American naval dominance quickly grew from there on.

Whilst Ahab was a king of Israel, whose name in Hebrew means 'brother of the father', I take the view that Ahab is in fact a coded reference to Abraham. One of Israel's tributaries was Moab, captured by Ahab's father, Omri, when Omri was king. The real whale that Melville based his antagonist upon was known as Moche Dick. If we allow for the Moby in Moby Dick to be a near anagram of Moab, then Ahab can be considered a jumble of the first two syllables of Abraham. Ahab leads his crew on a suicidal mission to hunt down the white whale, from which only Ishmael survives to tell the tale, as his Islamic counterpart survived at the mercy of God's last minute reprieve. The 'brother of the father' is here transformed into the father himself.

Melville famously said of Moby Dick, 'I have written a wicked book and feel spotless as the lamb'. In dealing with every aspect of whales and whaling, Melville took wholesale from books on cetology (the study of whales), with entire sections of Moby Dick copied verbatim straight out of the scientific literature of the day. If Ahab is the father of obsession and Ishmael its son, then the author completes the trinity, as a spirit haunting the scene. We are reminded of the book's opening words. 'Call me Ishmael'. Call who Ishmael? The obsession of Ahab is the obsession of Ishmael is the obsession of Melville in glorious literary trinity. A wicked book indeed.

Melville famously said of Moby Dick, 'I have written a wicked book and feel spotless as the lamb'. In dealing with every aspect of whales and whaling, Melville took wholesale from books on cetology (the study of whales), with entire sections of Moby Dick copied verbatim straight out of the scientific literature of the day. If Ahab is the father of obsession and Ishmael its son, then the author completes the trinity, as a spirit haunting the scene. We are reminded of the book's opening words. 'Call me Ishmael'. Call who Ishmael? The obsession of Ahab is the obsession of Ishmael is the obsession of Melville in glorious literary trinity. A wicked book indeed.Returning to the chapter called, The Ship, Ishmael leaves Queequeg 'shut up with Yojo in our bedroom - for it seemed that it was some sort of Lent or Ramadan', which, 'though I applied myself to it several times, I never could master his liturgies and XXXIX Articles'. The XXXIX Articles refers to the doctrines of the Church of England, but here again we see Dante's motifs of three and nine in action. We saw earlier how the names of the three whaling ships hiring crew for three year voyages are each repeated three times in sequence. Once Ishmael has decided upon the Pequod, the ship's name is then repeated a further ten times, being mentioned a total of thirteen occasions within the chapter. XXXIX Articles divided by thirteen is three.

We are in danger of reading too much into things at this stage, which might indeed be the case. It might also be a result of the law of unintended consequence, the kind of happy coincidence which all writer's experience when attempting to make connections beneath the surface of their text. Like neural pathways, the more points there are to connect, the more possible connections there are to be made and the more things just happen by accident. Yet, this concordance between three and thirteen is also found at the beginning of Moby Dick and contributes to Melville's most perfect tribute to Dante and his Divine Comedy.

Just as the opening verse of The Divine Comedy serves a prologue to the comedy proper, so the opening three chapters serve as a prologue to Moby Dick. At the end of each respective passage, Dante meets his Virgil and Ishmael meets his Queequeg.

As we know, Moby Dick begins with the line, 'Call me Ishmael'. Ishmael goes on to say that having, 'nothing particular to interest me upon shore, I thought I would sail about a little and see the watery part of the world'. Yet having claimed to be interested in little upon the shore, it is more than eighty pages before The Pequod even sets sail.

From this initial paragraph, the remainder of the opening chapter drifts further and further away from the subject of the sea. Ish-Melville's digressions away from his theme begin apace. In the next three paragraphs he paints a picture of island of Manhattan (here called 'the city of Manhattoes', to remind us of the island's original inhabitants), with its 'thousands upon thousands of mortal men fixed in ocean reveries'. While many are transfixed by the water's hypnotic undulations, not one strays further than the extremities of the island's whale-like form.

'Once More' intones Ishmael and Loomings tries a third time to begin the novel. This time we are transported to some pastoral scene, far inland, far away from open sea. Yet even here the fixation with water is intensely felt. We are reminded of Narcissus, 'who because he could not grasp the tormenting, mild image he saw in the fountain, plunged into it and was drowned'. That 'tormenting, mild image' being the reflection of his own beauty. A torment considered mild when compared with Ahab's obsessions with the whale, which is the obsession with his own self image, magnified and engorged until it fills the seven seas entire.

At this third attempt, the narrative at last catches fire and we are on a roll. The opening paragraph leads to three descriptive paragraphs of Manhattan and then from 'Once more' to other end of the chapter is nine paragraphs long, expanding from one to three to nine. One, plus three, plus nine equals thirteen. One times three times nine gives us twenty seven. Which is nine.

The second chapter, The Carpet Bag is much shorter in length. Ishmael travels from Manhattan to New Bedford, where he misses the packet to Nantucket. He dispenses with this journey in a sentence, which tells us nothing of his voyage to New Bedford. Until Queequeg appears to guide us, we may know nothing of travel upon the sea.

The Carpet Bag concludes on the words, 'But no more of this blubbering now, we are going a-whaling, and there is plenty of that yet to come'. The third chapter, The Spouter-Inn is then nearly twice as long as the first two chapters combined. As previously explored, it acts as a microcosm of the entire book, Queequeg standing in as substitute for Moby Dick himself. In the three attempts to start the opening chapter, coupled with the three opening chapters that lead Ishmael to his first encounter with Queequeg, we travel through a three by three narrative matrix, which mirrors the opening verse of The Divine Comedy. Melville takes Dante's opening verse, adds a nine and makes it a perfect ten.

What Melville manages in the opening three chapters of Moby Dick, James Joyce achieves in the first page of Finnegans Wake. The Wake is rather a different prospect to either of its predecessors and yet it encompasses elements of both within its densely arcane text.

Finnegans Wake is the novel of a dream. This dream takes place during a single night and across the history of recorded time. As it is a dream, so the narrative takes the form of a dream. It is disjointed, allegorical, often impenetrable in its obscurity to the point where it has been dismissed as unreadable in many quarters, even within the Joycean world.

Yet while the Wake can be dismissed as a mess, it can also be seen as a rich, deeply complex work, which takes the form it does because it cannot be any other way. What's more, and contrary to popular opinion, it does definitely have a plot. A very simple plot. Finnegans Wake is the story of how men and women where at one time equal in society: equal in the foundation of the first settlements and cities. Then men invented the story of Adam and Eve and the fall of man and placed the blame for all of their sins squarely upon the shoulders of women. From then until now, woman has been relegated to a second class citizen.

We have seen how in Moby Dick, Herman Melville takes the legend of Narcissus and swells his self-obsession until it is as expansive as the seven seas. With Finnegans Wake, James Joyce takes all of recorded history and compresses it down to the size of one Dublin family. As the night progresses, the five family members come to personify myriad characters from world history and mythical tradition.

Hiding within the shadow play however is a second plot. One which has spilled over from the daytime world. The father, signified by the letters HCE (for ease of reference often called Humphrey Chimpden Earwicker, although his names are legion), has made incestuous advances upon his daughter, Issy. The mother, Anna Livia Plurabelle (ALP, again taking on many names and forms), has checked his drunken attempts by giving herself to him in the marital bed. As she lays there, bruised and now pregnant, she hopes against hope that tonight will be the night that HCE dies.

The Wake tells its story through a basic form of Freudian dream analysis. In The Interpretation of Dreams, Freud theorises that certain symbols signify elements of the real world, especially those of repressed sexuality. As we sleep, subconscious thoughts seep through into the conscious mind, but they go through a transformation in the process. At a very basic level, phallic images come to represent the penis, enclosed spaces like a door frame represent the vagina.

We know that Joyce had little time for psychology. His daughter, Lucia, named after Saint Lucia, suffered a series of mental episodes during her life and her father took her to see a number of psychiatrists, including the Swiss psychoanalyst, Carl Jung. Throughout, Joyce maintained that Lucia was perfectly sane and his already low opinion of psychiatry suffered all the more in his dealings with the profession.

The Wake makes a mockery of the world of men and employs many embodiments of patriarchal misogyny as part of its superstructure. As with Freudian dream analysis, phallic shapes in the Wake represent the male member, as well as man's dominance over women. Men and male history are also represented by the land, and its buildings and settlements. Woman, usurped from her position as joint founder of human civilisation, is pushed to the margins and is represented by water, most usually the River Liffey that flows through Dublin and out into the Irish Sea.

Yet as the Wake is a mockery of male history, it is, ultimately, told by a male author. As Moby Dick is a digressionary fisherman's tale, so the Wake is an attempt to tell the history of women (or at least an inclusionary history that takes into account the contribution of women), which frequently veers away from its topic. This is a dream after all and by their very nature dreams often change tack without warning. Unlike a dream, the Wake always realises it has drifted away and is constantly trying to reaffirm the narrative, sometimes lasting only a sentence, sometime a few pages at a time.

Finnegans Wake is a feminine history and as woman is represented by the river, so the words on the page are a river themselves. Words flow through the page and reading the Wake is like meditating upon a channel of water. At times the book is as formless and inconsequential as the sound of water running. Other times forms immerge from the surface to take shape and give meaning. The book has tides. The movement of words are not always in one direction. Oftentimes, sense can only be made by reading backwards clauses and phrases. On occasion, words even swirl in eddies and parts of a word will become detached and attach themselves to another word to create a whole new sense of what's going on.

Dante was one of the first writers to compose poetry in a local Italian dialect rather than the usual convention of writing in Latin. He inspired Geoffrey Chaucer, who wrote The Canterbury Tales in Middle English, eschewing the French that was still the official language of the English court at the time.

James Joyce, an expert linguist, employs syntax from more than sixty languages to form the narrative of Finnegans Wake. This allows Joyce to compress human history down into six hundred pages, with a word or sentence hovering between several meanings, depending on in which language individual sections are read. It also lends the text a more feminine form. To the male listener, a group of women talking simultaneously in a group can seem like a babble of words. Yet most women are perfectly capable of speaking and listening at the same, a throwback to humanity's hunter/gather origins. The Wake imitates the ability of women to multitask.

Reading the Wake, we are like Narcissus, obsessed and in love with our own reflection. We read of the fall of HCE and we assume the narrative is all about man. Yet there was another figure in the Narcissus myth, the figure of Echo. Echo was a wood nymph who so fell in love with Narcissus that she pined away until she was nothing, only her voice remaining.

We could take a different slant on the story of Echo and Narcissus. Maybe Echo was in fact the girlfriend of Narcissus (curiously, Bob Dylan's first girlfriend was called Echo). The lovers went to a secluded glade to be alone, but he espied his reflection in the pool and became so fixated by what he saw that he forgot all about Echo. She clamoured for his attention, but eventually stormed off shouting, "You treat me like I'm invisible." Thus was a legend born. Thus is the history of the world.

We hear of Echo frequently within the book, both by name and by words which reverberate backwards through the page (The echo is where in the back of the wodes; callhim forth!). Read forwards, they are the stuttering guilt of HCE. In the backwash, however, a stutter becomes the echoing voice of the river. Like Narcissus, like a yodeller in an alpine glade, man sees and hears only the reflection of his own presence. Indeed, most academic study has tended to ignore the female voice, the voice of Echo in Finnegans Wake, in favour of trying to ascertain what exactly is the nature of HCE's crime. Narcissus gazes upon his reflection and ignores the very substance which reflects it. The clues are all there and we can see them by returning to The Divine Comedy and how the number nine informs the opening chapter of Finnegans Wake.

The Wake opens on the lowercase word, 'riverrun'. We can see that this is not in fact a word. The Wake employs a series of portmanteau words, a class of word invented by Lewis Carol, as exemplified in the opening stanza of Jabberwocky:

`Twas brillig, and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe:

All mimsy were the borogoves,

And the mome raths outgrabe.

In Alice Through the Looking Glass, Humpty Dumpty explains to Alice, 'You see it's like a portmanteau—there are two meanings packed up into one word.' In the Wake, a phrase like, 'penisolate war', can refer to the Peninsular War, fought as part of the Napoleonic Wars. It can also refer to attempted rape. This phrase occurs during the second paragraph of the Wake and as reference to Issy appears in the middle of the word, 'penisolate war' more specifically refers to the attempted rape of his daughter by HCE (cf. in the same paragraph, 'avoice from afire bellowse mishe mishe', 'venissoon after', a bland old isaac', 'all's fair in vanessy','sosie sesthers') .

That being said, the opening word is not a portmanteau word at all, but rather two words jammed together. We know that the first half of the word represents woman. If we think of running as the kind of action which takes place on the land, 'run' signifies man. The opening word of Finnegans Wake then represents the perfect state, the time at which men and women held equal place. The history of civilisation is the history of the written word and in the first word of Joyce's General Theory of History, there is parity between the sexes.

As 'riverrun' represents parity, it also represents the outcome of the act of sexual union between man and woman. 'riverrun' is the fertilised egg nestling inside the womb. As the opening chapter of Moby Dick expands from one paragraph, to three, to nine, Finnegans Wake imitates cell mitosis, developing from a word, to a sentence, to an entire page. As the opening sentence develops, parity between the sexes is destroyed, replaced by the alternate creation myth of Adam and Eve. The opening sentence attempts to tell a unified version of human history, one in which female history is included, but masculinity stamps its authority all over the words, leaving HCE dominant by the end. The first sentence then reads:

riverrun, past Eve and Adam's, from swerve of shore to bend of bay, brings us by a commodius vicus of recirculation back to Howth Castle and Environs.

We can see that for this sentence to make real sense, 'past' should be spelt 'passed'. Yet in the river's swirling eddies, the opening two clauses should be read backwards:

Adam and Eve's past, riverrun

reminding us of the true history of our world. The river interacts with the land (the bay, the shore) and is diverted from its course. We hear references to the Emperor Commodious, who co-ruled the Roman Empire with his father, Marcus Aurelius, and to Gimabattista Vico, whose version of history posits that Noah's sons repopulated the Earth after the Biblical flood by impregnating the giant women who had survived the rising waters. Yet as a commode is also a toilet, the swirling eddies render and reorder 'a commodius vicus of recirculation' as a vicious recycling of the same old misogynistic shit.

Gimabattista Vico's other theory is that history moves through four cycles, the Age of Gods (Theocracy), the Age of Kings (Monarchy) and the Age of Man (Democracy), ending in the Ricorso, the age of chaos that exists before everything resets itself and the cycle begins again in earnest.

The opening page of Finnegans Wake contains three paragraphs, each telling and retelling how history was rewritten by its male victors, censoring mention of goddesses in the opening paragraph, queens in the second and finally women in general. This view is counterbalanced and undermined by the expansion from word to sentence to page, all of which adds up to a three by three matrix within the page. The opening paragraph is also the opening sentence. The opening sentence/paragraph is twenty seven words long. Two and seven make nine.

As a fertilised egg, the entire plot of Finnegans Wake is contained within its opening word (It is the same told of all. Many.). As the novel expands beyond the opening page, the same story is retold time and again, with many variations upon the theme, but always returning to 'riverrun', the 'meander tale', 'where, the tale rambles along' like the snaking course of the river. Before Adam and Eve, women held a position of equality and no matter how many times its author tries to change the subject, we always return to this narrative.

Joyce developed the narrative for Finnegans Wake from James George Frazer's classic work on comparative mythology, The Golden Bough. Frazer was confused by a few lines in book six of Virgil's Aeneid. Aeneas wishes to travel into the underworld to speak with his dead father. In order to do so, he is told he must pluck a branch from a certain tree, the so called golden bough, and present it to the keeper at the gates of Hades.

Frazer didn't understand why this was so and he discovered that at the time The Aeneid was composed, there was a temple in a woodland glade at Nemi, to the north of Rome. Nemi was a shrine to the goddess Diana, maintained by a priest who was known as The King of the Wood. The incumbent King of the Wood could only retain his position for as long as he could fend off any and all successors. Anyone who could break off a branch of a certain oak tree near the temple could challenge him to a duel. The incumbent therefore had to be on his guard at all times, often sleep deprived and paranoid.

Frazer's expansive investigation into this practice, the third edition is twelve volumes long and runs to over four thousand pages, uncovered the origin of many modern day secular and religious practices the world over. One aspect is how the role of king was originally a shamanistic one. The head of a village would be metaphorically wedded to the elemental goddess. He was expected to ensure the prosperity of the village, ample rain and a good harvest. Bad weather or a poor crop yield could mean his sacrificial death and replacement.

The Golden Bough concludes that originally women were the farmers in ancient societies. Frazer traces all corn rituals and corn goddesses back to two original goddesses, Demeter (Mother Earth) and her daughter, Persephone. In the original story, Demeter travels down into the underworld to locate her daughter and brings her back to the surface. If we think of how a seed is planted in the ground and later sprouts into a new crop, we can see how this story originated.

Frazer notes that as women originally worshipped goddesses and men gods, women must have been the first farmers and this was the story that the women of the earliest settlements began to tell. Therefore, it was women who gave birth to the first towns and villages and convinced their men to turn away from nomadic practices of following migrating pack animals.

Today we are familiar with the idea of a hunter-gatherer society and modern archaeological investigations have shown that the gatherers did indeed establish the first static settlements. However, the first edition of The Golden Bough was published in 1890 and relied on little more than a study of contemporary world mythology to reach its conclusions. It is a staggeringly impressive piece of detective work and one which inspired and appalled Victorian and Edwardian society in equal measure. Like The Divine Comedy, the influence of The Golden Bough is ingrained in our world, whether we realise its presence or no.

In Finnegans Wake, Demeter becomes Anna Livia Plurabelle and Persephone her daughter, Issy. The novel's final two characters, the twin sons Shem and Shaun, represent male dominance. Shem is a writer (Shem the Penman), Shaun a postman (Shaun the Post). They embody the ways in which history is recorded and communicated and how information is conveyed and controlled in a patriarchal society.

As The Aeneid inspired The Golden Bough, leading to the writing of Finnegans Wake, so The Aeneid had already cast its shadow upon Dante. Much of the structure and language of The Aeneid is to be found within The Divine Comedy. The Inferno in particular is a Christian inversion of Virgil's description of Hades (with much added by Dante himself). Perhaps the most famous line in all of The Divine Comedy, the words written at the entrance to hell (Canto III), 'Abandon hope, all you who enter', are inspired by lines from book six of The Aeneid, 'Abandon hope that the decrees of heaven may bend to prayer!'.

We also hear reference to incontinence and to the word, shades, to describe the dammed in hell. The word Empyrean is lifted straight out of The Aeneid. The same three beasts which affront Dante the Pilgrim in the opening Canto, the leopard, the lion, the she-wolf are also present, if only as pelt worn by its heroes. The she-wolf here is particularly female, an allusion to the wolf which suckled Romulus and Remus, the mythical twins, founders of Rome (cf. Shem and Shaun).

Despite Dante's insistence on the relationship between the number nine and Beatrice shaping the structure of his afterlife, threes and nines are to be found appearing all over The Aeneid. This in turn is Virgil referencing Homer, upon whose two epic poems The Aeneid is based. The first six books of The Aeneid reflect The Odyssey, the second six books The Iliad and The Iliad especially uses the number nine time and again, in praise to the nine muses who bless the classical Greek artistic forms. The Iliad also takes place during the ninth year of the siege of Troy.

There is a long standing tradition amongst writers of appropriating and inverting the work of their predecessors. In Homer, the sea based Odyssey is a sequel to the land based Iliad. In Virgil, Aeneas and his men are sea-going nomads for years before making land in Latium and battling against Turnus and his men, which reflects the Greek's siege of Troy.

Dante converts the Hades of Homer and Virgil into his Christian Hell. Melville makes hell the fo'c'sle of The Pequod. In Ulysses, James Joyce restages The Odyssey on land. In Finnegans Wake the history of civilisation takes to the water.

In The Divine Comedy, the foot of the island of Purgatory is guarded by the stoic philosopher, Cato. Cato tells Virgil that he must pluck a reed from the bank and tie it around Dante's waist. This will allow the pilgrim to pass safely through the gates of Purgatory. As soon as Virgil plucks the reed, another one immediately springs up in its place, mirroring The Aeneid, where another golden bough immediately replaces the one snapped off by Aeneas.

Cato was a supporter of Pompey, rival to Julius Caesar, who took his own life after Pompey's defeat rather than be ruled by Caesar. It's curious that Dante should choose a pagan suicide to guard the entrance to a place where Christian souls go to be purified and we see again how The Divine Comedy is a subjective journey to salvation rather than an objective vision of the Christian afterlife.

In Moby Dick, Cato appears in the opening paragraph, 'With a philosophical flourish Cato throws himself upon his sword; I quietly take to the ship' (note the definite article here, the ship, or The Ship, the chapter where the Pequod makes its first appearance). Ishmael then can be seen as moving in the opposite direction to Dante, starting on the banks of Purgatory with Cato and heading down into the Inferno with Ahab.

Stare beneath the surface and we also see Finnegans Wake inverting the themes of Moby Dick. In Moby Dick, the white whale beneath the waves is a manifestation of the colonial crimes of both Britain and the independent United States. The novel's densely symbolist text often alludes to slavery and to the genocide committed against the indigenous continental population, but never states it outright. The Pequot people are referred to as being extinct, but not how their extinction occurred. Even the name of the ship, The Pequod, is misspelt.

In the Wake, HCE is a sleeping giant beneath the land, his head under the Hill of Howth, overlooking Dublin Bay, his feet out beyond Phoenix Park, to the west. HCE's penis sticks up through the park itself and in the Wake's own dense symbolism, reference to an ambiguous crime committed within the grounds of the park is both an allusion to the framing of the Garden of Eden myth and to sexual violence against women in general.

HCE's placement beneath the surface of the Irish landscape mirrors that of Finn McCool, whom legend has it is buried beneath the Hill of Howth and who will one day rise to save the Irish people. Finn McCool is benevolent in the legend, yet the size of the Wake's giant, extending well beyond Howth, is a measure of man's misogyny, continuing the literary tradition of inversion. Having overthrown woman and removed her to the river, he now lies inert as she flows passed the city, a refugee from the place she once helped found, forced to be nomadic once more. HCE is under the ground both as a symbol of his laziness and of ALP's desire to see him dead and buried.

As neither book makes direct reference to its major theme, so the Wake fails to reference Moby Dick directly. Yet like the shapes which lie beneath the flowing water, allusions to the story of the white whale do on occasion break the surface. Ishmael appears briefly at the end of the first chapter of Part II, with three references in quick succession. Although as this is the Wake, Ishmael becomes Ismael, for reasons which should be obvious by now (Ismael = Issy) :

I hear, O Ismael, how they laud is only as my loud is one. If Nekulon shall be havonfalled surely Makal haven hevens. Go to, let us extell Makal, yea, let us exceedingly extell. Though you have lien amung your posspots my excellency is over Ismael. Great is him whom is over Ismael and he shall mekanek of Mak Nakulon. And he deed.

In patriarchal society, women are of value only for as long as they can bear children. Allusions to incest in Finnegans Wake also allude to fertile youth usurping barren old age. 'Great is him whom is over Ismael' encapsulates this, with its double reference to positions of patriarchal power and to hunched sexual domination. 'riverrun' subverts this notion by presenting the mother, not daughter, as the one who is pregnant.

HCE is a giant beneath the ground, as Moby Dick is a giant beneath the waves. HCE is often referred to with variations upon the name of Humphrey. Buried in his name we can infer a dig at man's inability to bear children, his freedom from the burden of bringing a child to term. A Humpback is a type of whale, which has fins that allow it to move through water, leaving a wake as it goes. The title of Finnegans Wake references an Irish wake and the condition of waking from a dream, yet it can also show the disturbance caused when man imposes his dominance over the watery world of women.

In Part I, Chapter iv of Finnegans Wake, the sentence, 'Heart alive!', briefly breaks the surface, with its allusions to Stubbs encouraging his crew to row faster in First Lowerings, 'Pull, pull, my fine hearts-alive; pull, my children; pull, my little ones', 'Three cheers, men - all hearts alive!'

The most interesting allusion however occurs in Part II, Chapter ii. The chapter takes the form of a school textbook, as the three children are at lessons. Perhaps the most difficult chapter of the entire book, as well as a central text, it includes chapter headings down one side, chapter points down the other, with a series of footnotes running through the text, all of which do their own thing and bear little relation to one other. On the chapter's penultimate page, we find this curious footnote:

2Wherry like a whaled prophet in a spookeerie

Immediately we are reminded of Hamlet's tormenting of Polonius:

Hamlet: Do you see yonder cloud that's almost in shape of a camel?

Polonius: By th' Mass, and 'tis like a camel, indeed.

Hamlet: Methinks it is like a weasel.

Polonius: It is backed like a weasel.

Hamlet: Or like a whale.

Polonius: Very like a whale.

'Very like a whale' takes its place amongst the list of quotes included in the Extracts of Moby Dick. Clouds in the Wake are a manifestation of Issy, the embryonic river, the girl who will be woman.

The most famous 'whaled prophet' was Job, who was swallowed by a whale or giant fish. However, we can also spot reference to Ishmael here, the whaling narrator of Moby Dick who shares his name with the Biblical prophet, father of the twelve tribes of Islam.

The Islamic references run deeper. The holiest prophet of Islam is of course Mohammed. These days, Islam places an absolute ban on images of Mohammed, but during the Middle Ages images of the prophet were commonplace, usually with a veil drawn across his face. Three prophets for the price of one.

Islam and Christianity have greatly influenced each other over the centuries and it was the gradual immergence of the image of Christ upon the cross during the Middle Ages which led to images of Mohammed being banned. The Caliphs at that time saw how Christians were coming to worship the image of Christ crucified, a violation of the second commandment. 'you shall not make for yourself a graven image', and banned similar images amongst their followers. However, the ban was only ever meant to apply to Muslims and, ironically, the terminal intensity with which some of the more fundamentalist sections react to non-Muslims making inflammatory images is exactly the kind of the thing that the Medieval Caliphs were trying to avoid. The absence of a graven image has itself become a graven image.

References to Islam and the veil bring us back to the treatment of women. During the 1920s and 1930s, at the time Joyce was composing Finnegans Wake, the Middle East was a more moderate place than we find today. Increasing reliance on oil in the years following World War Two led western countries to forcibly replace progressive, moderate democracies with hardline dictatorships. Joyce died in 1941. However, one of the other major influences on the Wake is The 1001 Tales of the Arabian Nights (1001 pleasingly being 9 in binary).

The mistreatment of women within the Middle East and India at the time is central to the overarching narrative of The Arabian Nights. Shahrazad staves off her own execution by her husband, the king, by each night telling him a story that ends on a cliff-hanger. Veiled women are commonplace in these tales, but scenes of modesty often end in debauchery. The Tale of the Porter and the Three Women of Baghdad begins with a veiled women buying delicacies from the market place, but soon descends into drunken orgy, the eponymous Porter made to guess the name of each of the ladies' private parts in turn ('Basil of the Bridges', 'Husked Sesame Seed', 'The Khan of Abu Mansur').

And what are we to make of the curious word, spookeerie? Aside from calling to mind a haunting (eerily spooked), we can also think of an eerie as the name for an eagle's nest, a bird's nest. A ship too has a bird's nest high up in the mast and in Moby Dick an entire chapter, an entire digression even, is devoted to standing watch in the mast-head. Given Moby Dick's coded references to slavery, the first half of spookeerie could be a reference to the derogatory term for black people and a spookeerie is therefore a position from which to watch over slaves. In Dutch, spook is a derogatory term for an annoying women. Spookeerie then becomes a position to watch over and spy upon women (be an earwigger - Humphrey Chimpden Earwicker). A cry of 'There she blows' comes from the spookeerie and the whale watcher becomes the slave holder, becomes the possessor of woman. Don't you just love literature.

The structure and movement of The Divine Comedy is always through circles. As well as the nine circles of hell and nine concentric heavenly spheres, the island of Purgatory is conical and Dante and Virgil go around each of its nine levels and up successive flights of steps in climbing towards the Garden of Eden. It has also been argued that the entire arc of The Divine Comedy moves through a circle, beginning and ending in heaven, with the Virgin Mary sending Lucia to Beatrice to find Virgil to rescue Dante.

Ahab takes his crew around the world and down into the circuitous rivers of hell, but kills all but one before the circle is made complete.

In the children's textbook in Part II, Chapter ii of Finnegans Wake, Joyce placed this geometric diagram:

Two intersecting circles describe an ellipse, inside which two equilateral triangles are formed, ALP and αλπ, upper case and lower case Greek, mother and daughter, Anna Livia Plurabelle and Issy. Mother and daughter replace father and son in Joyce's version of the holy trinity. Whereas Melville makes himself his own holy ghost, it is Joyce's own daughter, Lucia, the Wake's muse, who is the book's insubstantial spirit. Whenever the text references Issy, an allusion to Lucia is usually to be found haunting the scene nearby (Issy-la-Chapelle! Any lucans, please?). Her full name was Lucia Anna Joyce, but due to a mix up her birth certificate recorded her as Anna Lucia Joyce. Moreover, Lucia's parents did not marry until many years after she was born and she should really have taken her mother's maiden name, Barnacle. Anna Lucia Barnacle contains the same number of syllables as Anna Livia Plurabelle.

Anna Livia is represented by the water and Issy by clouds. Here again we see circular movement, with water evaporating from the sea to form clouds, falling as rain on the hills, flowing downhill and forming into the river and back out into the sea.

Plurabelle can be taken to mean 'everywoman', but as 'belle' is French for girl, 'plurie' French for rain and 'plurer' meaning to cry, Plurabelle can also be taken to mean the girl of rain or girl of sorrow (cf. Our Lady of Sorrows in reference to the Virgin Mary). Plurabelle is then Anna's maiden name or matronymic name, recalling both her youth and the history of women. This subverts the use of the more usual patronymic, as found in names like Jameson, Johnson, or McCool. Issy, as well as referring the Egyptian goddess Isis (a corn goddess), is also Isabelle (is a belle), the cloud girl who will fall as rain and become Plurabelle, with a life of sorrow ahead of her. Such is the cycle of life.

In placing Isabelle in the clouds, Joyce once again inverts world history. The original name of the goddess Demeter would have been Gemeter. Ge, like geo, means earth. Meter, like mater, means mother. Demeter - Gemeter - Mother Earth, to remind us of the time when women tilled the land.

The full name of the Greek god, Zeus, was originally Zeu pater, meaning father Zeus or sky father. Jupiter, father Jove, was once Iupiter, sky father (piter here meaning father). Sanskrit also has a word, Dyau piter, also meaning sky father, which comes into Old English as Tiw, from where modern English gets the word, Tuesday. All of these words have their origin in an Indo European phrase, Dyeus peter, meaning father of the daytime sky, our linguistic roots identifying our ancestors as sun worshipers. Words like day, diurnal and divine all come from the same root word.

Men once looked to the sky for divinity. Women found life through planting and harvest. Later, men took over the job of farming and women were left with only the pain of childbirth and original sin. God came down from the sky and took up residence in temples and churches. With the position now vacant, Joyce relocates his heroines to rain and river, the most elemental of all life's essentials. As life began in the sea, so man was born of woman, as again reflected in 'riverrun', with the word's self-contained directional flow from water to land. Without womb or water, human existence would not be possible.

As Finnegans Wake begins on an unfinished sentence, so it ends the same way:

A way, a lone, a last, a loved, a long the

which is completed by the first sentence, making the novel a great circle. However, I prefer to see the book as open ended. Finnegans Wake begins on the lower case, riverrun, both to signify that there was human history before the invention of the written word and also to contrast a softer, more generous, less authoritarian past, before written history and the patriarchy of HCE and his religious misogyny. The book ends unfinished because history is unfinished, taking not a circuitous path but more akin to an always advancing wavefront.

In fact, it is the law of unintended consequences which makes Finnegans Wake more like a strand of DNA than anything else, although Crick and Watson would not formulate their double helix model until more than a decade after the book's publication and the untimely death of James Joyce. Evolution is occurring at all times in the Wake, phrases, songs and slogans repeating throughout, but always mutating as they go. The book opens with parity and ends with the daughter fearing a return to the father (my mad cold feary father), but the final word could also be seen as a mutation of she, a single mutated letter, with the final lines also reading:

A way, a lone, a last, a loved, a long she

The story then has two possible endings, either the whole cycle will begin again (end and begin again, Fin-again) or she will break free of the patriarch and wake an independent woman, alone at last.

As Finnegans Wake anticipates Crick and Watson, so the hidden name, as well as something of the popular image of Ahab, prophesised the coming of the end of the American slave trade. Abraham Lincoln would not be elected President of the United States until ten years after Moby Dick was published and the American Civil War would start soon after. The White House would ultimately be the one to slay the white whale. Little would change for the African-American population in the years following the civil war and America's second literary masterpiece, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, would be written in response to the situation in the south in the post war years. Huckleberry Finn is the New Testament to Moby Dick's Old Testament.

The Divine Comedy is a poetic sequence of diminishing returns. The Inferno is immensely entertaining, Purgatory merely interesting, Paradise, full of harmony and soul's contented with their lot, kind of a bore. The Inferno is the most endearing section of Dante's Comedy and the one most subject to cultural reference. Run 'The Divine Comedy illustration' through a search engine and virtually every result will be an image of the Inferno.

It can be argued that it was the broadcast in the 1980s of such films as Threads and When the Wind Blows that showed western audiences something of the horror of nuclear attack and led to greater efforts to bring the Cold War to an end. By staring over hell's lip and into the abyss, we can know something of ourselves. Perhaps even find redemption.

Addendum XXXIX

You may also like

Bough-Wake

Bloomsday 2011

Eden Stir Her Laceless Veil

The Hill of Howth

No comments:

Post a Comment