When I think of how and when I first read some of my favourite books;

some of my favourite authors, more often than not those initial experiences

came through a Penguin Books edition.

Reading Frankenstein in the custard yellow £1 Popular Classics edition. Reading The Raven and The Rime of the Ancient Mariner in 60 pence Penguin mini booklets. The Collected Essays, Journalism, and Letters of George Orwell, bought as a student from a second hand bookshop for £10 of precious food money; the orange spines of the four mouldering volumes bound together in a crisscross of elasticated rubber.

I have an aversion to all kinds of marketing and brand loyalty and yet

Penguin Books have probably had a greater influence on my development as an adult

than any other corporate entity.

I wasn’t much of a reader as a child. I had phases and obsessions like

everyone else, but it never seemed to last very long. I was twenty eight before

I even finished The Lord of the Rings, having read The Hobbit at the age of

eleven, which was to all intents and purposes the first real book I ever read.

An edition borrowed from a neighbouring child, shocked I hadn’t read it. I want

to say it was a Penguin or Puffin edition, but I don’t think it was. I don’t

really remember.

Partly because of the Hobbit, partly because of that childhood friend,

my first real obsession was Choose Your Own Adventure books, especially the

Fighting Fantasy series. During the time that I read them, those books were

published by Puffin, the children’s wing of Penguin. I collected the first two dozen

FF books in the series, as well as the guides and special editions, all of them

displayed in a glass fronted bookcase in the same way that adults display

commemorative plates. I still have my original copy of House of Hell, having still

not completed it after nearly forty years of trying. I was never very good at

computer games either.

Into my late teens and early twenties, I read fewer Penguin editions

than any time before or since. For a time I was obsessed with horror novelists,

reading Pan edition James Herbert novels bought from local market stalls,

before progressing to the superior Clive Barker books bought new. The James

Herbert novels are since consigned to charity shops. The Barker novels,

however, are still an important part of my collection. My Harper Collins

paperbacks are in serious state of disrepair. The opening pages in some cases are

held together by sellotape, I have read and reread them so many times over the

years. Yet they retain a prominent place on my bookshelves.

Having read little as a child, I stared to read more and more as I

progressed into adulthood. Moreover, I began to collect (some might say hoard)

books. Those custard yellow classics become an important and cheap source of

reading material. As well as Frankenstein, I read Edgar Allen Poe, Gulliver’s

Travels and Mrs Dalloway in similar volumes. Penguin published a parallel

series of poetry books in power blue covers. Through those editions I first

read Keats and Blake, as well as the war poets and the romantics.

One December, home from university, I presented my mother with a list of

seven or eight Charles Dickens novels I wanted as Christmas presents, expecting

her to choose two or three from the list. I received the lot, made up of the

custard yellow editions. Not bad for a total outlay of less than I had recently

spent on the collected Orwell. Those books stayed with me for years, until they

were replaced by my great uncle’s centenary edition of Dickens’s complete works,

passed on by relatives who knew I would take care of them.

At university, I developed a true collecting obsession borne out of

sentimentality and gratitude. Penguin Modern Classics book were at the time printed

with mint green covers. In those editions, I first read all of Orwell’s novels,

as well as his trilogy of socialist non-fiction: Down and Out in Paris and

London, The Road to Wigan Pier, and Homage to Catalonia. I bought my first copy

of Ulysses from a second hand bookshop in Cardiff on the way home from lectures

and my first copy of Finnegans Wake brand new from the local Waterstones, both

in those mint green editions. I ate up Ulysses in no time, but it would be more

than a decade before I finished Finnegans Wake (which still makes it an easier

read than House of Hell).

In those same mint covers, I read Kafka’s The Trail, Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman and The Crucible, and three of Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe novels in one volume. Penguin replaced the mint green editions more than twenty years ago, but I still rescue copies from secondhand bookshops, even if I don’t know the book or the author. As such, I have read Collette’s Collected Stories, the Letters and Journals of Katherine Mansfield, and Tadeusz Borowski’s darkly comic holocaust stories, This Way for the Gas Ladies and Gentlemen, when each might have been missed in favour of books and authors more well known to me. Even now, a collection of DH Lawrence’s short stories in mint green sits on one of my many To Read piles.

The silver editions that replaced the mint green Penguin Modern Classics

seem less romantic, but it is less to do with aesthetics as it is personal

history and the rosy tinted view with which we regard first experiences. Like

first love or the particular incarnation by which we are introduced to a film

franchise, how we experience anything for the first time leaves a indelible imprint

on the imagination. The First Love Fallacy.

The mint green editions hold a special place in my heart and yet it was

in the silver editions that I first read East of Eden, which remains my

favourite Steinbeck novel (and one of my favourite novels of all time). I own

most of Steinbeck’s fiction and non-fiction and the books that aren’t in old

Pan or Grafton editions are all silver Penguins. See also, the second volume of

Philip Marlowe novels. Allen Ginsberg’s Deliberate Prowse. Philip K Dick’s, The

Man in the High Castle.

Over the years, I’ve also picked up older Penguin Classics and Modern

Penguin Classics from secondhand bookshops across the country. Before mint

green, the modern classic novels were grey and white with the only colour

coming from the cubist and modernist cover artwork. These were my introduction

to Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, the second and third volumes of Sartre’s Road

to Freedom the trilogy (the first part, The Age of Reason, sits among the mint

greens), and Brave New World.

While collecting secondhand books, I began a trend that started out as

an accident but has become something of a superstitious habit. One of my

favourite authors is Fyodor Dostoyevsky. I own copies of most of his novels,

shorter and non-fiction, but I do not own any two books that are published by

the same publisher and in the same edition.

Like the modern classics, the regular Penguin classics have changed over

the years, so that I have a copy of Notes from the Underground and The Double

printed together in a black Penguin Classics edition; a copy of The House of

the Dead in the previous black and yellow covers; and several other books in

earlier editions.

My copies of The Brothers Karamazov and Demons are published by Oxford

University Press, but in subtly different editions. My version of the Idiot is

printed by Wordsworth. I also have various other novels and short story

collections in paperback and hardback from a hodge podge of publishers. It has

become something I take far too seriously. That I cannot obtain a new

Dostoyevsky book unless it is from a publisher or in an edition I don’t already

own. No reason for it. Just because.

In arranging my books, I organise by publisher first, then edition, then

alphabetically from right to left (some weird quirk of being left handed). It

is the Penguin editions that occupy the central bookcase in my library, with classic

and modern classic box sets sitting on top. I have collected so many Penguin

books, there isn’t room for them all on the shelves and they overspill to lie

sideways on top of the other rows.

Other publishers are available. Yet the default for any book available

from multiple publishers will always be Penguin. I once bought a copy of War

and Peace in a Wordsworth edition from a charity shop. However, the text was

far too small and the font and paper quality used by Wordsworth always seem to

cause me problems. The Count of Monte Cristo in a similar edition took months

to get through, forever delaying the reading for something with better quality

print. Which is a pity, because The Count of Monte Cristo is a masterpiece.

As such, I replaced the War and Peace Wordsworth with a two volume

Penguin edition from a secondhand bookshop. Then I was able to read all 1,666

pages in four days over a long weekend. More impressively, I didn’t get through

even a hundred pages on one of those days. More than five hundred pages a day

over the other three. A personal record.

Other than Penguin, I have constructed what I consider an impressive

library over the years. Books bought brand new and from charity and secondhand

bookshops. Some special editions from the likes of Folio Book that cost a lot

at the time but which have only accumulated in value over the years. In a

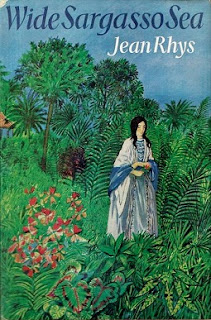

charity shop in Sunderland in 2000, I bought a copy of Wide Sargasso Sea for

25p. From what I can tell, the book is part of an early print run of the first

edition and worth a couple of hundred pounds.

Such finds are rare and in the Internet Age less likely to be missed by booksellers. But everyone can build a private library for relatively little money, if you know the right places to look. In one place where I lived, there were two places within walking distance that were practically giving books away. Five books for a pound in one charity shop that was only open on certain weekends. I found so many books there I would often throw them money on the way past even when I wasn’t buying anything. There I got a massive French dictionary for 20p. Also, a Penguin classics boxset, including Wuthering Heights, Pride and Prejudice, and Robinson Crusoe that was mine for £1. It sits like a monolith on top of the Penguin bookcase.

The other place was even better (or worse). Essentially a junk shop with

boxes of books of which the owner just wanted to get rid. My housemate found it

and dragged me there to pan through boxes, looking for gold. I would take a

backpack with me to fill up with on Pan Agatha Christie books and come away

with change from a £2 coin.

When I used to visit family in Liverpool, I had a walk planned out where

I could visit four or five bookshops in a one hour circuit. One of my nine

copies Moby Dick (the correct number of Moby Dicks one should own) came from

those foraging expeditions. Also, Jason Burke’s excellent history on Al-Qaeda.

One birthday in 2005, I took myself on a trip to Hay-on-Wye. A cold,

dark February. Largely deserted. Spending two days wandering around the town’s

plethora of bookshops. So many options. So many choices to make. Buying the

first Foundation books. Schindler’s Ark. Chandler’s final, unfinished Philip

Marlowe novel, Playback. Seeing books like Brenda Maddox’s biography of Nora

Joyce that I would buy online many years later.

A strange trip. Getting the train to Hereford. Sat reading the

introduction to the Cambridge Press edition of Hamlet in a café, waiting for

one of the handful of buses a day that go to Hay-on-Wye. Filled to the gills on

Full English Breakfasts and my ear talked off by the landlady of the bed and

breakfast where I was staying. Meaning to go back some day. A day yet to come.

How many other books have I bought on similar trips? Da Vinci biography

from Clos Lucé. Chomsky in Florence. A Griel Marcus book on Dylan from

Greenwich Village. Not to mention the many bookshops to be found in Amsterdam.

I remember one place I stumbled upon, which consisted mainly of Dutch language books. However, there was one lone bookshelf of English language editions. One shelf was almost entirely filled with Paul Auster novels. I was distraught. I wanted them all, but only had limited space in my backpack. I had to make do with a sole copy of Leviathan.

In Amsterdam’s American Book Exchange, many an American edition can be

found. American and Canadian backpackers bring them with them from across the

Atlantic and swap them out for newer books from the same shop. A treasure trove

of secondhand books, replete with basement repository of science fiction and

horror novels. One of my favourite places to idle away an afternoon, racked

with indecision and guilt for those I leave behind.

Of course, the Mecca of European bookshops is the Parisian Shakespeare

and Company, opposite Notre Dame cathedral. Not the original Shakespeare and

Company, but baring the same name as Sylvia Beech’s shop that stood on the rue

de l’Odéon until it was closed in 1941 following the Nazi invasion of France.

From that original location, Ulysses was first published, Beech

financing its printing and publication. Not only a bookshop, but a lending

library, Beech’s Shakespeare and Company was a familiar haunt for many writer’s

of the so-called Lost Generation. Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Gertrude Stein, all

borrowed books from Beech with varying levels

of diligence about returning them on time. Hemingway was apparently one of the

worst.

The original location is now a boutique, but George Whitman opened the

current Shakespeare and Company in 1951 and continued to run it until his death

in 2011. Part of the ritual of a transaction is to receive a Shakespeare and

Company stamp on the flyleaf of the book you have bought. I have a few such

books, but my copy of Campbell and Robinson’s A Skeleton Key to Finnegans Wake takes

pride of place.

As well as physical bookshops, there are many places that sell books

online. Although Abe Books is unfortunately owned by Amazon billionaire, Jeff

Bezos, it is undoubtedly a valuable source for finding rare books that are

otherwise out of print. As a reader and amateur scholar of James Joyce, I have

found many reference books via Abe Books that I couldn’t have found anywhere

else. I own three glossaries of the Gaelic, German, and Scandinavian words in

Finnegan Wake, each of which are former library books and which had over the

decades been borrowed a total of eight times between them before being

withdrawn and put up for sale. I have also been able to find cheap, well

preserved copies of most of the standard academic texts on Finnegans Wake from

the same site.

My father was a great reader, though our tastes are somewhat divergent.

He had a large collection of books on the kings and queens of England and was an

avid collector of books on Horatio Nelson. Still, I did inherit from him my

first copies of the collected Shakespeare and Oscar Wilde, as well as two

copies of the collected Sherlock Holmes stories.

Many of his books were given to his local model building society after

he died, but a few remained. Among these was a handful of Time Life Seafarers

books that had stood on the bookshelves since the late 70s. Large black

hardbacks, filled with glossy pictures. I often flipped through those books as

a kid, enjoying the books on pirates and Vikings the most, like any boy with a

vivid imagination. At some point I set out to actually read those books. Being

more than forty years old, the veracity of the text has slipped somewhat, if it

was ever very accurate to begin with.

Still, they are enjoyable for what they are and I wondered how many more

there were in the series other than the ten we owned. A little research revealed

a total of twenty two volumes. With the help of Abe Books, I set out to

complete the set. Most were bought for a few pence plus postage and packaging

from places like Tallahassee Public Library. All in remarkably good condition.

Books that I will probably never read again, but like collecting mint green

Penguin Modern Classic editions, the endeavour was done for entirely sentimental

reasons. If nothing else, they serve as ballast at the bottom of one of my myriad

bookcases.

I dislike brand loyalty and yet more of the books on my shelves are

Penguin than of any other publisher. I drink out of a Bonjour Trieste cup. I

have a cupboard full of similar Penguin Books mugs. I have boxes of postcards

displaying Penguin covers that are affixed to the exposed sides of my

bookcases.

Penguin were the first company in the UK to print cheap paperback

editions of the classics and make them accessible to mainstream audiences. In

1960 they dared the wrath of the UK censors by publishing Lady Chatterley’s

Lover and went to court to defend the public’s right to read it.

British and international readers owe Penguin an enormous debt of gratitude, not only for printing all kinds of paperback novels, but for filling the secondhand bookshops of the world with books that are in constant state of recycling. For hoarders like me, who are not rich and yet want to read and display the books twe have read, Penguin are an invaluable resource. As such, anyone can build a private library on a budget, should they so desire.

Read More