...And it's a graphic

novel...

Except it's not a novel: It's a

potted history of the North East of England. Principally it tells the tale of

the city of Sunderland's influence on the imagination of Lewis Carroll. Though

that's like calling Ulysses the story of a man who goes for a walk. It

digresses and it deviates into everything from a dissection of the Bayeux

Tapestry to an examination of public art on display on the Sunderland waterfront;

the Viking invaders and vandals at Lindisfarne to the Hartlepool Monkey,

taking in every artistic style from

Hergé to Hogarth along the way. There's full comic strip interludes, an

intermission and a big musical finale. Yet the thread that holds it all

together, that every narrative arc coils around, is Lewis Carroll.

Bryan Talbot is one of the founding fathers of British

Graphic art. A professional illustrator since the late 1960s, Talbot has had a

prolific career over the years. He has illustrated everything from Neil

Gaiman's Sandman to staple characters like Nemesis the Warlock and Judge Dredd

for 2000ad. More recently he co-produced 'Dotter of her Father's Eye', a graphic

novel with his wife. It depicts Mary Talbot's early life, growing up with her father,

the Joycean scholar, James Atherton. Wound around this is the tale of the relationship

between Joyce and his own daughter, Lucia. It amply demonstrates what a broad

church the comic book genre has become in the 21st century. From Scott Pilgrim

to Shakespeare, all of human imagination is to be found here.

Talbot though has made his name through his solo works. The

pan-dimensional steam-punk romp, 'The Adventures of Luther Arkwright' is

sublime and along with 'When the Wind Blows' is generally regarded as one of

the first graphic novels published by a British artist. What makes him a

pioneer of graphic art is his roving mind and his wide palate. 'The Tale of One

Bad Rat', released in 1995, deals with homelessness and child abuse: Grandville,

his ongoing detective series, centres on Detective Inspector LeBrock, an

anthropomorphised Badger with a taste for meting out violent, summary justice.

The third book in the series, 'Grandville Bette Noir', is due for release in

December.

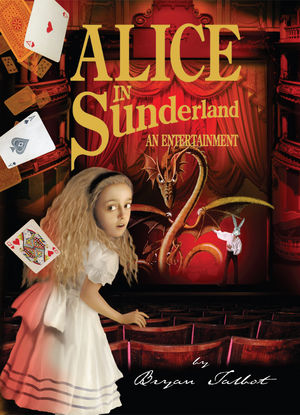

There's also 'Alice in Sunderland'.

I first encountered 'Alice in Sunderland' watching 'Comics

Britannia', BBC Four's three part documentary on the history of the UK comic

industry. I love comics. Growing up on naval estates, no Christmas stocking was

complete without the Battle annual. We'd unwrap it at midnight and climb to bed

to read tales of plucky Tommies fighting behind enemy lines.

There was also 'The Beano' and 'The Dandy', which I read well

past the age at which I was meant to be too grown up for such childishness. Turns

out I wasn't the only one.

Yet the comic that has stayed with me right into adulthood

is 2000ad. There's something uncompromising and unpatronising about 2000ad. It's

partly the era in which it was founded. The recession and constant threat of nuclear

war cast a dark shadow over Britain in the 1970s and this is reflected in the characters

that emerged over the years. In Judge Dredd I first encountered the idea of a

dystopian future, long before Brave New World or Nineteen Eighty-Four. 2000ad

was a godsend for a boy with an overactive imagination and an obsession with

science fiction. It led me to Jules Verne and Philip K Dick. And in time literature

led me back to comics.

I was researching a short story where the heroine was meant

to be ephemeral. She was originally going to be a comic book character, but I

can't draw for toffee, so I made her a fictional character instead. To heighten

her ephemeral nature, I wanted to have a series of illustrations to accompany

the text. I decided to have a look at some graphic art and get some ideas while

I worked on the story and then find an artist when I was finished.

I read some classics (2000ad collections, Alan Moore novels,

Maus) and the story formed in my mind. And then Comic Britannia started, its

first two parts chronicling everything I had read as a kid, The Beano, The

Dandy, Commando and Battle. And in the final part was everything that I had

been reading since reconnecting with the genre. The only inclusion that was new

to me was Alice in Sunderland.

I ordered a copy online but it failed to arrive. And then we

heard that Bryan Talbot was giving a talk in Manchester off the back of the BBC

Four programme. We went along to watch and I was bought a copy of the book to

get signed. Talbot inscribed it and drew a Mad Hatter in gold pen. A few days

later I started reading.

Now, maybe it's just that it appeals to my interests and

deals with an area I know so well, my brother having moved to Sunderland over

fifteen years ago, but I do think that Alice in Sunderland is one of the true

masterpieces of this still relatively young genre. There's Maus and Footnotes

in Gaza to add to that list, both of which deal with historical atrocities in

strikingly different styles. And Watchmen, which has yet to be surpassed in storyline,

even twenty five years after its release. It is frequently cited on lists of

the 100 greatest novels of all time. Writer Alan Moore and illustrator Dave Gibson

are both former contributors to 2000ad.

Alice in Sunderland is different though. It's lavish. If

Watchmen gives good narrative then Alice in Sunderland delivers the visual feast.

It drifts in style, black and white to full colour, traditional comic strip to

digital photography, sometimes in frames, sometimes spilling out to encompass

the entire page. It has a page drawn by the legendary Leo Baxendale, the man

who created the Bash Street Kids for The Beano. There's also a comic rendering

of Henry V's 'Once more unto the breach' speech, as well as digressions into

fully contained tales like The Lambert Worm and Jack Crawford, The Hero of

Camperdown. Even a comic strip version of Lewis Carroll's Jabberwocky.

To try and describe the book as simply as possible, there

this bloke, who is Bryan Talbot, who goes to a theatre, which is empty, to

watch a performance given by a man, who is also Bryan Talbot. The entire thing

is part lecture, part vaudeville performance. It centres on Sunderland and the

Sunderland Empire, which is a hundred years old that evening, but sweeps out to

encompass London and Scandinavia in its widening gyre. It also connects Oxford

to Sunderland, for Lewis Carroll had family in the North East and apparently

spent many holidays in the area. Some of its geographical features may even

have inspired elements of the Alice books.

There is a third version of Talbot, the Pilgrim, who breaks

out of the confines of the theatre and rows up the river Wear and travels back

in time and gives guided tours of real locations in the city and environs. It's

a book filled with history, packed to the rafters with maps and photographs and

reproductions of John Tenniel's illustrations for the Alice novels. Lewis

Carroll gave few actual descriptions of the characters that Alice encounters in Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass and they owe much

of their popular imaginary to John Tenniel's artwork, which was

published in the original editions.

From John Tenniel, Alice in Sunderland spins out into all

the other artists inspired by Alice and through all the other mediums that have

attempted to capture her essence, from theatre to cartoon, Dali to Lennon,

Jabberwocky to The Matrix. Yet like any good storyteller, Talbot also includes the

personal. His hometown Wigan is woven into the fabric of the story with

connections back through George Orwell and George Formby and Talbot's memories

of his gran. And aside from Lewis Carroll, the central thread on which the

story hangs is that of a regretful elder man addressing his younger self, one

of a number of universal themes explored in Alice in Sunderland.

Yet because this is a book about Alice, it is also about

dreams. We see the author awake in the middle of the plot, panicking about the

insanity of drawing a dream. We see the action spontaneously change scene and

change topic and the ghosts of long dead comic actors rise from the grave. The

overall structure is more ordered than a dream. The book is often discursive

but never irrelevant. It seeks only to inform as it entertains and creates an

intensely personal document as it does so.

The personal is ultimately what appeals to me about Alice in

Sunderland. It is a singular one-off performance. The traditional graphic novel

couldn't achieve the same effect, it would be too hampered by the need to

advance the storyline and conform to conventional plots. There are many graphic

novels, the best amongst them, that could ultimately be boiled down to

description purely by words. Not so Alice in Sunderland. It is a book and a

concept that absolutely needs to be a graphic novel. It would be almost

impossible to do it any other way. It takes the ephemera of the dreaming world,

the ephemera of alice, of

Carroll, of Cambridge, Wigan and Sunderland and creates a book like a funfair

ride, one that can seem to be spinning out of control, but is always within the

artist's grasp. It demonstrates how much history can be found in your own

backyard and how everything in the universe ultimately connects back to

everything else. If I had to take one graphic novel to a desert island, it

would be Alice in Sunderland.

I'm no technophobe (I'm permanently plugged into the

internet via one device or another), but I do prefer to experience certain

things in the traditional way. I don't think I'll ever be converted to the

Kindle or other e-readers. I prefer lamp lit to backlit. I enjoy the smell of

paper, turning the page in anticipation of what is to come. It's almost like a

ritual, a reassurance that whatever happens there are always more books to

read. Much as I love technology, books needs to access the tactile senses in

order to help the connection between writer and reader form. To hold a book

like Alice in Sunderland, with its A4 format and its glossy, heavy pages and

hardback spine, is to feel that need satiated. Talbot calls the book an

entertainment, but it's more than that, it's an event, the way reading should

be. Read it and then revisit sections at your leisure to tease out the details.

The best books you have to read more than once. That's why they're the best,

because they keep on giving.

I'm no technophobe (I'm permanently plugged into the

internet via one device or another), but I do prefer to experience certain

things in the traditional way. I don't think I'll ever be converted to the

Kindle or other e-readers. I prefer lamp lit to backlit. I enjoy the smell of

paper, turning the page in anticipation of what is to come. It's almost like a

ritual, a reassurance that whatever happens there are always more books to

read. Much as I love technology, books needs to access the tactile senses in

order to help the connection between writer and reader form. To hold a book

like Alice in Sunderland, with its A4 format and its glossy, heavy pages and

hardback spine, is to feel that need satiated. Talbot calls the book an

entertainment, but it's more than that, it's an event, the way reading should

be. Read it and then revisit sections at your leisure to tease out the details.

The best books you have to read more than once. That's why they're the best,

because they keep on giving.Alice in Sunderland is book for anyone with a curious mind and a thirst for knowledge. It's like watching an entire series of QI on DVD; it's witty and informative with the occasional minor mistake (the Hartlepool Monkey is almost certainly an urban legend that came down from Scotland in ballad form). Yet I love it all the more for that. Print media may well be moribund, but graphic novels should prevail long after what's left of the medium had died out. Comic books and graphic novels aren't merely for reading, they are for collecting. And that signed first edition of Alice in Sunderland that sits on my bookcase takes pride of place.

Postscript: I wrote the short story. It is called A Woman of

Conviction. I still don't have an artist. Contact me if you are an artist or

know of anyone who would like to get involved.

Four More One Offs

Britten and Brulightly

On the face of it a

private detective procedural, the action follows Fernandez Britten after he is

hired to investigate a suicide. Britten's partner, Brulightly, is a talking

teabag. Good old fashioned film noir with a damp British tint.

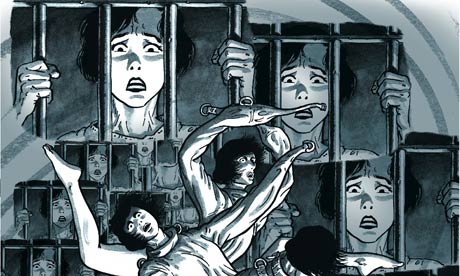

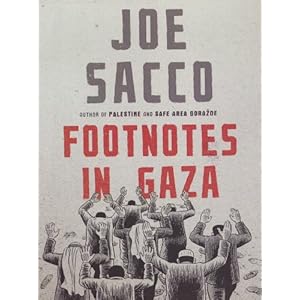

Footnotes in Gaza

Investigative

journalist Joe Sacco presents his enquiries in comic book form. In 'Footnotes

in Gaza' he sets out to investigate the massacre of 111 Palestinian refugees by

Israeli forces in Rafah in 1956. As Sacco's investigation proceeds the

continuing conflicts in the region are never far away. A great epic of a

graphic novel at over 400 pages, every panel is drawn with passion and purpose.

Maus

Art Spiegelman

turns the Germans into cats and the Jews into mice in order to document his

father's experiences as a prisoner in Auschwitz. And yet despite the

anthropomorphised characters, 'Maus' realistically treats its subject matter,

showing the every day of the camp, the common place, as well as its horrific

ultimate purpose. A breakthrough publication.

William Blake: The Complete Illuminated Books

Long before comic

books were invented, William Blake was printing and self-publishing his poems

as illuminated books in Lambeth. 'The Marriage of Heaven and Hell', 'Songs of

Innocence', 'The First Book of Urizen' and others classic poems can only be

truly appreciated when you have seen then them as Blake envisaged them, with

embellishments and illustrations. 'The Complete Illuminated Books' is as

exactly as it states.