Having recently completed a reread of James Joyce’s Dubliners, I decided to rewatch The Dead, John Huston’s film adaptation of the story of the same name. Although I have seen the film at least twice before and read Dubliners countless times, this is the first time of experiencing them in close proximity to one another. Which makes comparing them considerably easier.

The Dead is the final story in the series of fifteen that make up Dubliners. It is easily the longest of the set, running to more than fifteen thousand words, and revisits many of the same themes found in the rest of the collection. Paralysis. Jealousy. Youthful folly. Alcoholic excess. Simmering resentment. It is considered by many to be one of the greatest short stories ever written.

The 1987 film adaptation of The Dead was the last film completed by director, John Huston, before his death later that year. It is the denouement to a career that spanned forty six years, including such films as, The African Queen (1951), The Misfits (1961), Casino Royale (1967), The Man Who Would Be King (1975) and Escape to Victory (1981).

However, it is Huston’s debut feature, The Maltese Falcon (1941) that, for me, remains one of the greatest films ever made. It is a movie so engrained in my consciousness that even when I return to the novel (which I have read almost as many times as Dubliners), I visualise it in black and white, despite the rich palate of colours described by Dashiell Hammett’s prose. Sam Spade’s yellow-grey eyes shine through the greyscale like a character in a Sin City movie.

|

| Old Yellow-Gray Eyes |

The party actually takes place on 6 January, the Feast of Epiphany, also known as Little Christmas, or Nollaig na mBan in Gaelic, meaning Women’s Christmas, when the Christmas period was over (6 January is also Twelfth Night) and it was the turn of the women of the household to celebrate.

During Little Christmas, men would take on the duties traditionally assigned to the women in a variation on the Lord of Misrule Christmas traditions, where the masters serve the servants. It should be noted that in neither the story or the film adaptation of The Dead is there much evidence of the male characters taking on these roles, or contributing much to the preparations. They are too absorbed by their own petty concerns.

On the surface, the story of The Dead is fairly simple.

Gabriel and Greta arrive late. Gabriel is to give an after-dinner speech, as he

has done at the annual gathering for a number of years. Gabriel works as a

teacher and part time journalist. He fusses over the details of his speech, rejecting

sections for being too high brow for the tastes of his audience.

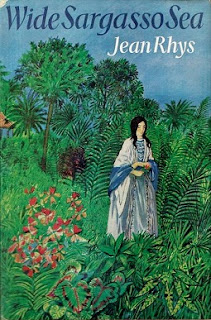

My 1st copy of Dubliners

Gabriel is teased by Miss Ivors for being a ‘West Briton’, a term of abuse used for those more interested in European rather than Irish culture. She tries to convince him to make “a trip to the west of Ireland.” He refuses. Greta tries to convince him to go, so she can return to Galway, where she grew up, but Gabriel tells her she should go on her own, or with Miss Ivors, if she so wants.

There is dancing and music recitals. The character, Freddy Malins, shows up drunk, to the chagrin of the hostesses and his mother, who is visiting from Glasgow. Dinner is served and Gabriel gives his speech to universal acclaim.

As the Conways are preparing to leave, Gabriel finds Greta listening to the tenor singer, Bartell D'Arcy, sing ‘The Lass of Aughrim’ (a traditional Scots/ English ballad), as if lost in thought. When he asks here about it at the hotel where they are to spend the night, she tells him about Michael Furey. Furey used to sing ‘The Lass of Aughrim’ for her when she was a girl and they were courting. He died when he was only seventeen. Greta believes he died because of her, after he showed up to her house in the pouring rain on the night before she was due to leave Galway for Dublin. He refused to leave and already being sick, passed away several days later.

Greta becomes distraught as she tells Gabriel about Furey and cries herself to sleep. The story and film end with Gabriel standing by the window as he laments never having loved anyone enough to die for them. Snow is falling outside and Gabriel’s consciousness sweeps across the whole of Ireland, from the ‘dark central plain’ to ‘the lonely churchyard on the hill where Michael Furey lay buried.’ Gabriel’s inner-monologue ends the film in a voice over largely taken verbatim from the closing words of the story (with changes from the third to first person).

A simple story it might be, but the power and the glory of The Dead and Dubliners in general is often what is left unsaid. What is hinted at and alluded to between the words. It is no wonder Ernest Hemingway adored Dubliners and used the stories as touchstones for his own short fiction. If anyone could rival Joyce in leaving things unsaid, it was surely Hemingway.

However, the film loses some of the subtlety of Joyce’s prose. Which is always the trade off when adapting the written word for the screen. What this means in practice is that the film version contains a lot that is essentially padding to bulk out the story to a running time of eighty minutes (John Huston’s son, Tony, who wrote the script notes that the first draft, an almost verbatim rendering of the story, came in at about a forty five minute runtime). Some of it works and some of it does not.

Watching the film with the story fresh n my mind, the elements I find most superfluous and more than a little hammy are in the treatment of Greta. In the story, Greta is pretty much caught unawares in hearing ‘The Lass of Aughrim’ after so many years. This plummets her into the black mood that renders her mute during their journey back to the hotel. In the film, however, there are several moments where something someone says causes her to remember Furey and primes her for the moment on the stairs.

Angelica Huston as Greta is fabulous in the role, but I find all the wistful looks a little grating as they lay it on thick for the audience. It’s not like the audience knows what’s going on, unless they are already familiar with the story. This somewhat dilutes the impact of the moment on the stairs.

Moreover, the depiction of the key scene is a bit on the nose with the way Huston is lit. In the story, Gabriel doesn’t recognise his wife for a moment, standing there in the semi-darkness. The film version leaves no-one, not even Gabriel, in any doubt as to who is on the stairs.

|

| Where? There on the stair. Where on the stair? Right there. |

Given the time in which the film was made and the febrile political situation in Northern Ireland at the time, as well as the financial support the IRA received from America’s Irish population, this is surely deliberate. A nod to nationalism: Of which, I think it is safe to say, Joyce would not have approved. One has only to read the Cyclops episode of Ulysses to find a clue to his opinion on such matters.

Indeed, there are these odd moments that seem to play into an idealised theme park version of Ireland found in the United States. It’s not quite leprechauns stealing me lucky charms and dying everything green, but the score can’t help but include strains of the kind of diddly-dee ‘Irish music’ you find in many tired, clichéd depictions of Irish life, from John Ford’s The Quiet Man to divers episodes of Star Trek.

The irony that Colm Meaney, who played Chief Miles O’Brien in both Star Trek: The Next Generation and Star Trek: Deep Space 9, appears as Raymond Bergin is worth mentioning in passing. The familiar Star Trek trope known as, O’Brien Must Suffer, includes Meaney being made to suffer through many of those tortuously clichéd Star Trek scenes (see The Next Generation episode, Up the Long Ladder, for instance, which is painful to watch).

The Dead is the epitome of refinement by comparison. Meaney’s performance is understated. He is very much a secondary character, but no true Star Trek fan can help but follow him as he dances in circles around the room in the background. As a Joyce and a Trek fan, I am always happy when the two intersect (as with the Deep Space 9, Quark, who, like the fundamental particle, takes his name directly from Finnegans Wake).

Mr Grace is the one character added to film who

doesn’t appear in Joyce’s story. It has been suggested he was partly included

to give him some of Mr Browne’s lines and make the latter a more overtly comic character. Browne is the

only protestant character in the story, which might also have something to do

with it, making him more a more scornful character to play to the predominantly

Catholic Irish American audience.

Chief (right), what are you doing here?

Mr Grace performs one of the set piece of the film, a poem he says is called, ‘Broken Vows’ (which facilitates one of Greta’s moments of misty eyed wistfulness). Sean McClory, who played Mr Grace, coincidentally, appeared in The Quiet Man as Owen Glynn.

Another set piece comes when Aunt Julia sings a warbled voiced version of ‘Arrayed for the Bridal’, and the camera sweeps the rooms of the house, alighting on various items, from photos and needlepoint, to vases, candlesticks and porcelain angels.

I feel these are the additions that Joyce would appreciate. Music was always a part of Joyce’s life. He might have been a successful opera singer if he hadn’t chosen writing (and his terrible eyesight hadn’t precluded sight reading). His books are filled to the brim with music and the moments of recital feel as much a nod to Ulyssean episodes like Sirens as anything else. It is easy to see how much John Huston was influenced by Ulysses (his mother smuggled him a copy of the book out of France when it was still banned in the US).

The other main criticism one might make of the film adaption is that it somewhat diminishes Gabriel’s place in the story. He is still the most important character in the film, but Joyce’s story is much more focused upon him. For the most part, he is as much a point of view character as others found in Dubliners (cf. Eveline, After the Race, A Painful Case, etc.). The comic elements around Browne and Malins, as well as the set pieces, defocus Gabriel centrality to a large extent.

However, Greta is much more present in the film

version. Despite the hammy elements of her various reminiscences, Angelica

Huston’s portrayal makes Greta all the more sensual than the rather staid woman

found in Joyce’s story. Joyce wrote better female characters later in his

career, most notably Molly Bloom in Ulysses. As Joyce largely based both

characters on his wife, Nora Barnacle, it is apt that Huston plays Greta closer

to Molly than the actual character in The Dead.

Joyce very much based Gabriel on himself with Gabriel’s

cycling trips to the continent to brush up on his French and German. Joyce’s

degree was in modern languages (French, German and Italian). He and Nora lived

on the continent for all but the first few months of their relationship. Though

I can’t quite imagine Joyce on a bicycle. His eyesight was too bad for that.

Nora Barnacle

Donal McCann as Gabriel isn’t very Joyce like. Joyce was tall and skinny. McCann is shorter and stocky. Although both Joyce and McCann died tragically young in their 50s.Yet McCann is perfect in the role and it’s as difficult to imagine Gabriel as anyone else as it is to imagine anyone but Humphrey Bogart being Sam Spade.

It has its issues, but the film version of The Dead is still satisfying to watch. To those of us who read and reread Joyce, study him and learn at his knee and who lament his reputation as being difficult and opaque and not more widely read as a result, any cinematic representation of Joyce’s world is gratifying. It would be nice if someone would produce an anthology from the rest of Dubliners, with different directors tackling one story each. However, it seems unlikely.

So other than Joseph Strick’s 1967 version of Ulysses, which I still haven’t seen, The Dead is about the best we are going to get. Joyceans celebrate Epiphany as the first date in the Joyce calendar and some even hold a recreation of the meal and celebration featured in The Dead. I will settle for reading the story and watching the film.

Then again, I was born on 2

February, which is Candlemass, Groundhog Day, and also James Joyce’a birthday. Which is a pretty good birthday to have. And a damn good celebration.

Other Books on Film