In common with Nick Cave, I have little time for popularity contests. That said, the contest for Album of the Year 2011 was effectively over by mid-February with the release of PJ Harvey’s masterpiece, ‘Let England Shake’. Universally acknowledged as an instant classic the album’s almost spectral soundscape serves as perfect backdrop to Harvey’s evocative lyrics; lyrics that deal with the singer’s often tempestuous relationship with her country, especially at times of war.

While much attention was drawn to the aspects of

‘Let England Shake’ that deal with war, less was to be said about its lament to

a nation’s decline. Perhaps the reviewers all felt too embarrassed, as the

English generally are when it comes to discussing patriotism. Yet while PJ

Harvey saves her most graphic images in capturing the consequences of conflict,

the one word that reverberates throughout ‘Let England Shake’ sits at the core

of its very title. England is the heart and soul here; the bringer of shame (you leave a taste, a bitter one) and yet

even in its greyness and its grime it is the daydream of soldiers sat

stagnating in battles past and present.

Oh America. Oh

England.

'Let England Shake' is not a jingoistic album. A

difficult balance is maintained between passionate cry and dispassionate

appraisal; between the love of the land, the acceptance of its shortcomings and

the disapproval at its darker episodes. England, that name resounds through the

three opening tracks. Songs that are sung in eulogy of better days, that conjure

Blakean visions of the Thames ‘glistening like gold’ in the memories of battle

scarred minds, that chide the US and UK in disappointing tones for the orphans

that their wars have left untendered (What

is the glorious fruit of our land? Its fruit is deformed children. What is the

glorious fruit of our land? Its fruit is orphaned children).

Personally, I have a troubled relationship with

the country of my birth. Technically I am Scottish, my submariner father having

been stationed at Faslane when I arrived, mewling, into this world. For years

after coming south, I clung to a pseudo-Scots identity, especially after moving

to East Lancashire, where anyone born further away than Rishton was treated

with idle suspicion (see Modern Epilogue). With my professed Celtic origins and

my accent cobbled together from half a dozen places we had lived in over the

years, I felt a perverse pleasure at being so alien in a place already so

suspicious of outsiders. There I heard casually spoken the kind of racist

vitriol that should have filled any rational being with revulsion, aimed

against people one barely saw really. That crystallised in me a certain hatred

for the English, with their petty mindedness and their hypocrisy and their

cries for fair play, unless it involved diddling some third world country out

of its natural resources. And I knew that it wasn’t so much that I wanted to be

Scottish as that I didn’t want to be English.

And here’s the nub of the matter. Generally people

aren’t looking for somewhere merely to belong, they’re looking for something to

rally against: To be in dynamic opposition against. That’s really why people go

to the football or form breakaway religious sects, so they can condemn and

abuse those who hold marginally different views to them. I was no different. I

had no Scottish friends, I was a member of no societies, I observed no

traditions or holidays, yet the fact that I was born in Scotland meant I wasn’t

English and I could wind up my English mates every time they got

unceremoniously dumped out of the latest footballing tournament. I felt an

affinity with the Asians in the town, paying special attention to be polite,

courteous and grateful in shops, in a futile attempt to show that not everyone

around here was gormless and ignorant. As usual I sided with what I perceived

as the underdog, a curiously British, if not English, trait.

I should’ve figured it out much sooner than I did,

but eventually I came to a solution. The people that I was angry with weren’t English.

They were working class men from a depressed, post-industrial northern town

that had had a new ethnic group introduced into its population right as the

town’s fortunes took a nose dive. Many mistakenly saw in that cause and effect

rather than symptoms of the same malaise. Ironically, it was the increase in

living standards that the mills brought to the towns of the north west that

ultimately led to mass immigration. Better schools meant better education,

which meant better prospects for the general population and the mills were

suddenly deprived of the factory fodder on which they had always relied, leading their owners to import cheap labour from the hot house of the sub-continent,

already acclimatised for the hot house of the mills. So when I look back on

those countless idiots spouting off about the trouble with the Asians, I can

take a perverse pleasure in knowing that the Asians probably wouldn’t be there

at all if these bozos’ parents hadn’t had the nerve to want their children to be

able to read.

The person who did more than anyone to force me to

confront and rethink my own prejudices was John. John was born and bred in this

part of the world and yet unlike most everyone else I knew he didn’t just look

out of his window, identify the first person that looked different to him and

heap all of his misfortunes on their shoulders. John wanted to be different. So

did I and that made us fast friends. That and a weird sense of humour.

Often we would sit up ‘til the early hours,

amusing ourselves writing spoof newspaper articles or offering continuous

commentary on the shit on late night TV or just talking into the early hours on

matters weighty and irrelevant. Time and again in these debates the same two

topics reared their confrontational heads: pride and nation. Their appearance

was always guaranteed to raise the stakes. John delighted in challenging my

notions of pride, which I saw as an entirely negative emotion. I kidded myself

that I preferred to be humble in my achievements, but really it was that I preferred

simple understatement for greatest effect.

Discussions of nation were always subdivided into

two sub-categories; a) John’s pride in his nation and b) Rob’s sniffy attitude

towards John’s pride in his nation:

J: I’m proud to be British.

R: Why?

J: Why? Because of warm beer and red post boxes

and cricket on the green, that’s why.

R is confused by

this. Post boxes are yellow in France, blue in the United States. So what? And

as he was to discover years later, post boxes in Britain were originally

painted green, but people kept walking into them.

I argued that if he took pride in anything as

random as the colour of a post box, he should also feel shame for slavery and

assorted other colonial crimes. John declined this invitation, stating that

slavery had nowt to do with him. I countered that the Royal Mail’s colour

scheme had little to do with him either, but he still seemed to want partial

credit. He’d put up a spirited defence and we’d argue over the main points again,

like running a biro over a well-worn shape on a pad.

Still, there was little that was said there that

failed to make its mark, no matter how stubbornly it was rejected at the time,

and over the years those same arguments sat fermenting at the back of my brain.

I expanded my scope beyond mere borders. It was useless to talk of England and

Scotland in this context. What were England and Scotland anyway? Northumbria

used to be part of Scotland and most of the north west was at one time part of

Wales. In order to be scientific, I had to consider a geographical region, not

an arbitrary, amorphous tax zone. That could only mean Great Britain at large.

While I could wriggle out of being English,

I couldn’t escape being British. It’s amazing how one’s attitude changes when

one is forced to integrate with that group (humour). Actually, I have to admit that I am

typically British in many ways. There’s the love of the plucky underdog, the

obsession with the weather, the twenty a day tea habit. People here are also

very tolerant, chiming well with my chosen philosophy, which states that what

people do behind closed doors is their own concern (excluding the abuse of

others). When comedian Richard Herring grew a toothbrush mustache in order to

gauge modern day public reaction to something synonymous with Hitler, he was

left pretty much unaccosted throughout the country. During the Second World War

that same toleration and love of the underdog led English publicans to refuse

US Army requests to segregate their premises. Segregation didn’t square with

British notions of fair play.

Which isn’t to say Britain always plays fair. The

concentration camp was a British idea; the first ever aerial bombardment of a

civilian target was committed when Britain bombed Iraq. And of course Britain

was heavily involved in the slave trade: the fortunes of its North American

colonies were predicated on slavery, as were those in the Caribbean.

However, it’s all too easy to get caught up in

post-colonial guilt and start to believe legends based on half-truth. While it

is true that British troops gave small pox blankets to Native American tribes

people, this was done as a gesture of good faith rather than genocide. The

small pox hospital in question was empty at the time and the British had no

need of the blankets. Meanwhile, it turns out a virus like small pox spreads by

person to person contact not through soiled linen. The Native Americans got

sick because they were exposed to diseases carried by Europeans from the Old

World, which is why in the end they tried to keep themselves to themselves

(until we went looking for them).

No matter how you divide or sub-divide a

community, you will always find good and bad at the margins, with the rest

regressing to a societal norm. Those wishing to lionise or demonise that

community look only to its margins, and to only one side at that, forming a

brand new nation in their minds as they do so (it’s the very confirmation of

the theory of confirmation bias). Yet before you can know where you're going,

or what you should be doing, you have to know where you are and how you got

there. More importantly, you have to accept where you are: be grounded in the

reality of where you are. And this brings me back to PJ Harvey.

While the disembodied voices of long dead soldiers

echo through its halls, ‘Let England Shake’ is an album for the here and now.

Harvey knows where England is and how it has arrived at this point. And she

knows its future looks bleak. I fear our

blood won’t rise again. Is it her fear or folksy acceptance of the

inevitable? It’s a damp, grey place, full of fog and graveyards and dead sea

captains and fetid alleys that host acts of drunken violence. And yet this is

home.

What's striking about ‘Let England Shake’ is how brutally

honest it is in its patriotism. It shows England at its most depressed and

holds it up as a thing of beauty. It’s a tough love to be sure, the way only a

parent can love a child, but it's the kind of national attitude I can tip my

hat to, in my tolerant British way. I don’t have to agree with the sentiment to

admire its honesty.

As with Polly Jean, so with John. John doesn’t

wear his national pride on his sleeve, he keeps it locked in his chest. You

won’t see him hanging a flag of St George on his car or out his window, but

he’s still proud of where he comes from. And how far he’s come. And despite my

still tricky relationship with pride, I’m proud of him too.

Isn’t it great

that we’re all better people?

As for me, I no longer suffer the same violent

reactions towards expressions of national pride. I still feel a little

uncomfortable when the bunting is hung out for international tournaments, but

I’ve long since come to realise that it has nowt to do with patriotism. The

individual, that’s who I always most wanted to be, the kid doing his own

thing. Of course large groups of people

united through a common focus make me uncomfortable, it goes against everything

in which I idiotically believe. Still, it’s a small price to pay, because while

it may be a way short of the best, Britain is a better place to live than most.

It is still one of the very few places in the world where one can be an

individual without harassment from religious or political authority. And in

that respect at least, I attribute my British passport to good fortune.

Ultimately it comes down to familiarity. It’s familiar here. It would be the same wherever I was born. Yet before you can know where you are going, you have to know where you are; be grounded in the reality of where you are. Yes, I was born in Britain. I attach no pride or shame to that event. It was a long time ago and I don't really remember that much about it. It's fine. Moving on...

Ultimately it comes down to familiarity. It’s familiar here. It would be the same wherever I was born. Yet before you can know where you are going, you have to know where you are; be grounded in the reality of where you are. Yes, I was born in Britain. I attach no pride or shame to that event. It was a long time ago and I don't really remember that much about it. It's fine. Moving on...

The West's; asleep, the West's asleep-

Alas! and well may Erin weep,

That Connaught lies in slumber deep.

But-hark! -some voice like thunder spake:

"The West's awake, the West's awake'-

Sing oh! hurra! let England quake,

We'll watch till death for Erin's sake!"

Alas! and well may Erin weep,

That Connaught lies in slumber deep.

But-hark! -some voice like thunder spake:

"The West's awake, the West's awake'-

Sing oh! hurra! let England quake,

We'll watch till death for Erin's sake!"

II

Even seen from the distance of two centuries, Goya series of prints 'The Disasters of War' still have the capacity to shock. They depict the numerous atrocities that both sides committed during Napoleon's invasion of Spain. It's hard to know how much of what Goya drew he actually witnessed, but he reproduces each scene with visceral immediacy. Executed men tied to posts, pathways littered with corpses, body parts hanging from trees; it makes one thankful we live in such a sedate corner of the world these days.

Europe was entrenched in yet another war at the beginning of the nineteenth century. It was a time when politics fired artistic passions. French artist David had helped unleash the guillotine upon the aristocracy during the 'Terror' and now fawned over Napoleon. Beethoven had idolised Napoleon, but turned against him upon hearing he'd declared himself Emperor. Tchaikovsky celebrated the beginning of his downfall with the appropriately triumphant '1812 Overture' and Tolstoy wrote at length about the affair long after it was all over.

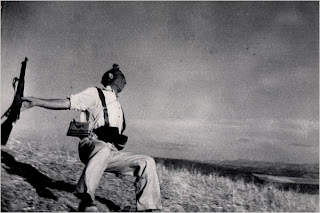

Although not displayed until long after Goya's death, 'The Disasters of War' were one of the first attempts at a kind of documentary photography. Long before the invention of the camera, Goya was sketching in sharp focus. There is much of 'The Disasters of War' in the photography of Robert Capa and Don McCullin. The images were also influential in the mind of one PJ Harvey.

|

| 'arms and legs were in the trees' |

For as long as men have gone to war, they have sought to recreate the experience through a variety of artistic forms. Writing, painting, music, photography and film have all been employed to varying effects to capture something of the sights, sounds and smells, the sensory overload and outright dislocation of battle, rendered knowable for the benefit of those thankful to be spared its horror. The twentieth century saw slaughter conducted on an industrial scale from its beginning to its end. Wilfred Owen equated the men conducting the First World War with Abraham going against God's commandment and slaughtering his son, 'and half the seed of Europe, one by one', in a return to the practice of human sacrifice. He died a week before the Armistice was signed.

What passing-bells for those who die like cattle?

Only the monstrous anger of the guns.

Only the stuttering rifles' rapid rattle

Can patter out their hasty orisons.

Poetry was still in vogue back then, as it had been since the rise of Napoleon, and for many in Britain what was happening over the channel was first communicated to them through the poetry of Owen, as well as Siegfried Sassoon, Robert Graves and Rupert Broke. Today they are as part of the national conscious as Shakespeare or Blake. Poetry's influence would decline over the years as new forms of entertainment were invented, but the war poets impact is so great that they are almost mandatory on any English Literature course in Britain. Tune in to any radio or TV station around 11th November to hear them recited as part of Remembrance Sunday commemorations. Like Homer's Iliad, they capture the boredom and the inertia that sets in between the violence.

If I should die, think only this of me:

That there's some corner of a foreign field

That is forever England.

While the English related their experiences through verse, other nations turned to prose. American Ernest Hemingway used his time as an ambulance driver on the Italian Front as the basis for his 1929 novel, 'A Farewell to Arms'. Hemingway was badly injured by a mortar shell and the book focuses on his alter ego, Henry, and his relationship with the nurse who tends him back to health. It's a romantic novel, told in that tough, plain way that Hemingway is famous for, but he doesn't shy away from the grim realities of war.

German, Erich Maria Remarque gives us a perspective from the other side of the trenches. 'All Quiet on the Western Front' humanises the 'enemy', shows him as being subject to same propaganda, witness to the same horrors, paralysed by the same terrors. The Nazis burned it on their pyres of banned books.

'Johnny Got His Gun' may be the greatest anti-war novel ever written. Indeed it is so powerful that it was banned during World War Two. A film version was made in 1971 and in 1987, fifty years after it was written, heavy metallers Metallica recorded, 'One', based on the novel. But then when it comes to approximating war, there really is only heavy metal can do it justice (see Slayer's 'War Ensemble', habitually used by US troops in pumping themselves up for battle).

With 'Let England Shake' there is no attempt at approximating the feel of war, merely an attempt to present a soundtrack against which to project its voices. PJ Harvey's lyrics call to mind many conflicts, but time and again they return to World War One. She knows the old adage that those who refuse to learn the mistakes of the past are doomed forever to repeat them and deliberately comes back to a conflict that is now a century in the nation's past. History repeats itself. There was death then, there is death now. A hundred years ago young men were massacred by their millions on the fields of Belgium and France. Today those figures are dramatically reduced. Yet whereas the vast majority of war casualties used to be soldiers, today they are mostly civilians. Not that we even call them wars anymore. Wars have battlefields.

Often neglected in history lessons is the Spanish Civil War that broke out in 1936. And yet as in Napoleonic Europe and the trenches of the First World War, it set artistic passions ablaze. It was a place to which to rush and defend from the fascist forces of the Nationalists. George Orwell joined the POUM Militia, a leftist Spanish political party. He wrote 'Homage to Catalonia' about his experiences, including being shot in throat and witnessing the street fighting that broke out in Barcelona and pitted factions in the left against one another.

Hemingway made propaganda films for the Republicans and in 1940 published the novel, 'For Whom the Bell Tolls', the tale of an American soldier who joins a group of Spanish guerillas to dynamite a bridge used by Franco's fascists. It's another tough tale from our Ernest and his most accomplished. The English poet Laurie Lee meanwhile had been tramping around the Spanish countryside at the outbreak of war and at the end of 'As I Walked Out One Midsummer's Evening' his hosts are endeavoring to find him passage out of the war zone. In 'A Moment of War', Lee depicts his journey back into Spain to try and join the fight. He is imprisoned as a Nationalist spy, then released to join the International Brigade. After anticipating battle for so long, he finally kills an enemy soldier in a skirmish and decides war is not for him.

The Spanish Civil War is a fascinating moment in history because it was the first concerted effort against the rising menace of fascism upon the continent. Hitler was an opportunist, he gained territory by chancing his arm and getting away with it. The elites of Europe were still trying appease him and hoped he'd go away. Read the literature of the day and it seems it was already to clear to many by 1936 that war between Germany and Great Britain was inevitable. Spain was a first chance to take the fight to the fascists.

And in the spirit of Goya, the defining image of the Spanish Civil War, one of the defining images of art in the twentieth century, is Picasso's 'Guernica'. Picasso painted 'Guernica' in response to the bombing of the Basque village of the same name by German and Italian planes. You don't really appreciate the impact of' Guernica' until you have seen it up close and personal. The canvas is enormous, the twisted, tortured faces filling the vision. It's no wonder the copy in the UN was covered up when Colin Powell came to plead his case for war with Iraq.

Yet the warnings were not heeded and we all know the result. The slaughter of the Second World War was once again on an industrial scale. The consequences and the aftereffects reverberated through the Suez Crisis and Korea, into the Vietnam War. More tons of TNT was dropped upon the counties of Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos than were dropped by all sides during World War Two, including both atomic bombs. The century ended as it began, with slaughter, and all that appeared to have changed was that we had outsourced the casualty figures to the 'enemy' of the day.

The twenty first century began with a bang, quite literally, and the shock wave from the attacks on 11th September 2001 have been circling the globe ever since. They should have caused us to pause and take a good long look at ourselves. Instead the same rhetoric was trotted out to push the same imperialistic ambitions that would have existed whether there was Osama Bin Laden and the Taliban or not. The war in Afghanistan has now gone on nearly twice as long as the Second World War, three times as long as the First World War, and few people understand what it's all about. Even if the reasons given for the invasion were accurate, they surely ceased to be relevant long ago.

PJ Harvey asks these questions. Her lyrics serve to show how no one involved in war benefits from its destruction. Family life is decimated, the fertile ground is ripped open, soldiers are haunted by the things they are ordered to do. Harvey uses the past to examine the future and ask why things seem to have changed so little in a hundred years.

Walker's in the wire, limbs point upwards, there are no birds singing 'The White Cliffs of Dover'.

Yet there is a glimmer of hope here. Noam Chomsky reminds us that things do tend to get better, despite concerted efforts to slow the pace of progress by those in power. We can, he notes, talk about differences of opinion within today's equal rights movement, yet try even talking about equal rights a century ago. The concept would have been baffling. Civilisation slowly evolves.

The two most thoughtfully polemic works written in response to the 9/11 attacks were both written by women: Suheir Hammad's 'First Writing Since' and Ani DiFranco's 'Self Evident'. Both were composed by Americans directing their anger back at their own nation and calling it to account. They actually asked how this could have happened and offered suggestions that didn't resort to simplistic accusations of jealously. They express the anger left by the attacks, but they ask for solutions that don't revolve around the same old cycles of death and retribution.

With PJ Harvey's 'Let England Shake' we have perhaps the most effective and succinct commentary on the wars of recent years. Until even recently women's only role in war was as grieving mothers or victims of invading armies. Finally they have achieved a voice. And there really is no way to say that without sounding patronising, because it should have of course been that way a long time ago. Yet this where we find ourselves.

The global arms industry is worth tens of trillions dollars each year and the international community at best ignore and at worst ferment local conflicts and fuel the trade in weapons (Chomsky and others argue that it was the outbreak of the Second World War that ended the Great Depression in America and the US economy has been reliant on its arms industry ever since). Austerity is everywhere and people still die like cattle and it can seem like we're sliding back to the days of the workhouse and trench warfare. Yet things still improve. Ultimately the will of the majority wins through, even if it does take a century of trying. History does not repeat itself, but moves in waves. It goes up and down, with some repetition, but is always moving forward, playing variations around the melody as it goes. History is the world's longest standing jazz solo.

It's refreshing to see an album written about such a controversial subject was lauded by the press upon release and found instant success. Only the Daily Mail seemed to misunderstand, saying 'Let England Shake' drew no conclusions about the Iraq War. That's the Mail for you. For the rest of us, it's good to be reminded how things still tend towards the better. And at the risk of repeating myself, before you can know where you're going, it's good to remind yourself of where you are. If you believe you're trapped in a vicious cycle, you will repeat the same mistakes forever. To know history is moving forward is begin to put the mistakes of the past behind you.

'Let England Shake' takes its place in the pantheon of crucial commentaries upon war. From Thucydides to Julius Caesar, Delacroix to Dali, The Clash singing of 'Spanish bombs in Andalucía' and Lemmy's uncharacteristically tender vocals on Motorhead's '1916', right up to PJ Harvey, each new addition to the genre freezes war as a moment in time for our appraisal and careful consideration. In these days of virtual online battlefields and drone bombers operated from halfway around the world, the western mind has become almost entirely removed from the consequences of war. Many are still affected by them, soldiers and civilians alike. The conflict in Afghanistan rumbles on into its thirteenth years with no end in sight. It may be the war-without-end predicted by George Orwell in Nineteen-Eighty Four. PJ Harvey is an antidote to the apathy felt towards wars being waged that barely affect European life. She reminds us of why we should feel aggrieved. Perhaps if we paid greater heed to our great war chroniclers, they might instruct us to a clearer path towards peace.

The concert ended with a standing ovation and we went away feeling that Polly Jean was well on her way to becoming a national treasure. Her idiosyncrasies developed over the years. Like wearing feather headdresses. Well if you going to be regarded a national treasure here, you have to develop a few eccentricities first. Ordinariness in our cultural icons just won't do.

Following years of intensive research into the history of British conflict, Harvey emerged in her mercurial new guise as messenger and medium to the ghosts of war. Despite their shifting styles, her previous albums had been strictly personal affairs, raw and introspective. With 'Let England Shake', she almost removes her voice from the action altogether, serving only as a conduit to the lyrics. With that comes a greater aloofness, you can see it in her live performances, standing separate from the band, remote and distant. It's all part of the drama. 'Let England Shake' is as much a piece of theatre as it is a piece of music. All so different from that nervous, carefree night in Manchester not so many years ago.

My favourite fact about PJ Harvey is that she used to send advance copies of her albums to Captain Beefheart. My least favourite fact is that Captain Beefheart didn't like 'Stories From the City, Stories From the Sea'. Which is a pity, 'cause I have a fondness for that one. It reconnected me with PJ Harvey. The album almost entirely passed me by for a couple of years. Indeed, Harvey was owed the award for Least Contested Mercury Music Award having previously received the award for Least Noticed Mercury Music Award. Even Harvey seems to have virtually disowned the album these days. It's easily the most commercial thing she's released, but a solid rock album with some great tunes. And even some of Beefheart's best albums were commercial. Commercial for Beefheart that is (see 'Clear Spot'). I wonder what he would have made of 'Let England Shake'.

The sides of 'Let England Shake' that are shaded by war are perhaps universal to all, but there are other sides that can only really be appreciated when you've lived here awhile. Like reading Orwell's 'The Road to Wigan Pier', it doesn't leave you feeling patriotic or ashamed, just presents you with a picture of Britain that you can recognise and understand.

Like 'Johnny Got His Gun' or 'The Third of May 1808', 'Let England Shake' will remain timeless in its relevance and appeal. It's an album that speaks of the times it was written in, but has a atmosphere that is itself timeless. There isn't another album that sounds anything like it. I can't wait to see what Harvey tries her hand at next. With Beefheart for a mentor, anything is possible. An opera on the life of Emma Goldman perhaps? Whatever it is, I only hope she doesn't need to spend four years researching the next one.

The Spanish Civil War is a fascinating moment in history because it was the first concerted effort against the rising menace of fascism upon the continent. Hitler was an opportunist, he gained territory by chancing his arm and getting away with it. The elites of Europe were still trying appease him and hoped he'd go away. Read the literature of the day and it seems it was already to clear to many by 1936 that war between Germany and Great Britain was inevitable. Spain was a first chance to take the fight to the fascists.

| |

| The Falling Soldier - Robert Capa |

|

| Guernica |

The twenty first century began with a bang, quite literally, and the shock wave from the attacks on 11th September 2001 have been circling the globe ever since. They should have caused us to pause and take a good long look at ourselves. Instead the same rhetoric was trotted out to push the same imperialistic ambitions that would have existed whether there was Osama Bin Laden and the Taliban or not. The war in Afghanistan has now gone on nearly twice as long as the Second World War, three times as long as the First World War, and few people understand what it's all about. Even if the reasons given for the invasion were accurate, they surely ceased to be relevant long ago.

PJ Harvey asks these questions. Her lyrics serve to show how no one involved in war benefits from its destruction. Family life is decimated, the fertile ground is ripped open, soldiers are haunted by the things they are ordered to do. Harvey uses the past to examine the future and ask why things seem to have changed so little in a hundred years.

Walker's in the wire, limbs point upwards, there are no birds singing 'The White Cliffs of Dover'.

Yet there is a glimmer of hope here. Noam Chomsky reminds us that things do tend to get better, despite concerted efforts to slow the pace of progress by those in power. We can, he notes, talk about differences of opinion within today's equal rights movement, yet try even talking about equal rights a century ago. The concept would have been baffling. Civilisation slowly evolves.

The two most thoughtfully polemic works written in response to the 9/11 attacks were both written by women: Suheir Hammad's 'First Writing Since' and Ani DiFranco's 'Self Evident'. Both were composed by Americans directing their anger back at their own nation and calling it to account. They actually asked how this could have happened and offered suggestions that didn't resort to simplistic accusations of jealously. They express the anger left by the attacks, but they ask for solutions that don't revolve around the same old cycles of death and retribution.

With PJ Harvey's 'Let England Shake' we have perhaps the most effective and succinct commentary on the wars of recent years. Until even recently women's only role in war was as grieving mothers or victims of invading armies. Finally they have achieved a voice. And there really is no way to say that without sounding patronising, because it should have of course been that way a long time ago. Yet this where we find ourselves.

The global arms industry is worth tens of trillions dollars each year and the international community at best ignore and at worst ferment local conflicts and fuel the trade in weapons (Chomsky and others argue that it was the outbreak of the Second World War that ended the Great Depression in America and the US economy has been reliant on its arms industry ever since). Austerity is everywhere and people still die like cattle and it can seem like we're sliding back to the days of the workhouse and trench warfare. Yet things still improve. Ultimately the will of the majority wins through, even if it does take a century of trying. History does not repeat itself, but moves in waves. It goes up and down, with some repetition, but is always moving forward, playing variations around the melody as it goes. History is the world's longest standing jazz solo.

It's refreshing to see an album written about such a controversial subject was lauded by the press upon release and found instant success. Only the Daily Mail seemed to misunderstand, saying 'Let England Shake' drew no conclusions about the Iraq War. That's the Mail for you. For the rest of us, it's good to be reminded how things still tend towards the better. And at the risk of repeating myself, before you can know where you're going, it's good to remind yourself of where you are. If you believe you're trapped in a vicious cycle, you will repeat the same mistakes forever. To know history is moving forward is begin to put the mistakes of the past behind you.

'Let England Shake' takes its place in the pantheon of crucial commentaries upon war. From Thucydides to Julius Caesar, Delacroix to Dali, The Clash singing of 'Spanish bombs in Andalucía' and Lemmy's uncharacteristically tender vocals on Motorhead's '1916', right up to PJ Harvey, each new addition to the genre freezes war as a moment in time for our appraisal and careful consideration. In these days of virtual online battlefields and drone bombers operated from halfway around the world, the western mind has become almost entirely removed from the consequences of war. Many are still affected by them, soldiers and civilians alike. The conflict in Afghanistan rumbles on into its thirteenth years with no end in sight. It may be the war-without-end predicted by George Orwell in Nineteen-Eighty Four. PJ Harvey is an antidote to the apathy felt towards wars being waged that barely affect European life. She reminds us of why we should feel aggrieved. Perhaps if we paid greater heed to our great war chroniclers, they might instruct us to a clearer path towards peace.

|

| Gassed - John Singer Sareant |

III

In common with with Nick Cave, I have little time for popularity contests. That said, it was

good to see 'Let England Shake' win the Mercury Music Prize. It was the most

predicable, least contested outcome in the brief history of the contest. PJ

Harvey became the first artist to win the award for a second time. She got to

enjoy this one. 'Stories from the City, Stories from the Sea' was announced

winner in somber tone on 11th September 2001. Harvey was in Washington DC on

the morning of the attacks. That experience began a decade long quest to understand

the consequences of the event and to make a definitive statement about it. That

the Mercury result never seemed in doubt is a testament to how well she

succeeded in her efforts.

I remember seeing PJ Harvey at Manchester's Bridgewater Hall around the time her previous album, 'White Chalk', came out. Standing alone on a stage usually occupied by the Halle Philharmonic Orchestra, she filled the hall with sound with nothing more than electric guitar and vocals. It was a little disconcerting at first to realise she was going to be performing alone, but spellbinding to hear songs like 'Rid of Me' and 'Big Exit' stripped of any backing, making Harvey work all the harder to match their intensity.

I remember seeing PJ Harvey at Manchester's Bridgewater Hall around the time her previous album, 'White Chalk', came out. Standing alone on a stage usually occupied by the Halle Philharmonic Orchestra, she filled the hall with sound with nothing more than electric guitar and vocals. It was a little disconcerting at first to realise she was going to be performing alone, but spellbinding to hear songs like 'Rid of Me' and 'Big Exit' stripped of any backing, making Harvey work all the harder to match their intensity.

She was chatty, nervous, confessing it terrified

her playing solo. Switching to piano, she kept time with a metronome,

apologising that she was still learning. It only added to the evening's charm. The

new album was more melodic, more melancholic than the driving guitar riffs of

her previous two offerings. Regret had replaced attitude. It was as she has

always done, switching styles, trying something new. Yet the elements that

would characterise the sound and the style of 'Let England Shake' were coming

together that evening: the prepared piano, the autoharp, the long flowing dress

of an Edwardian steam punk. The feather headdress was all she lacked at

that point.

The concert ended with a standing ovation and we went away feeling that Polly Jean was well on her way to becoming a national treasure. Her idiosyncrasies developed over the years. Like wearing feather headdresses. Well if you going to be regarded a national treasure here, you have to develop a few eccentricities first. Ordinariness in our cultural icons just won't do.

Following years of intensive research into the history of British conflict, Harvey emerged in her mercurial new guise as messenger and medium to the ghosts of war. Despite their shifting styles, her previous albums had been strictly personal affairs, raw and introspective. With 'Let England Shake', she almost removes her voice from the action altogether, serving only as a conduit to the lyrics. With that comes a greater aloofness, you can see it in her live performances, standing separate from the band, remote and distant. It's all part of the drama. 'Let England Shake' is as much a piece of theatre as it is a piece of music. All so different from that nervous, carefree night in Manchester not so many years ago.

My favourite fact about PJ Harvey is that she used to send advance copies of her albums to Captain Beefheart. My least favourite fact is that Captain Beefheart didn't like 'Stories From the City, Stories From the Sea'. Which is a pity, 'cause I have a fondness for that one. It reconnected me with PJ Harvey. The album almost entirely passed me by for a couple of years. Indeed, Harvey was owed the award for Least Contested Mercury Music Award having previously received the award for Least Noticed Mercury Music Award. Even Harvey seems to have virtually disowned the album these days. It's easily the most commercial thing she's released, but a solid rock album with some great tunes. And even some of Beefheart's best albums were commercial. Commercial for Beefheart that is (see 'Clear Spot'). I wonder what he would have made of 'Let England Shake'.

The sides of 'Let England Shake' that are shaded by war are perhaps universal to all, but there are other sides that can only really be appreciated when you've lived here awhile. Like reading Orwell's 'The Road to Wigan Pier', it doesn't leave you feeling patriotic or ashamed, just presents you with a picture of Britain that you can recognise and understand.

Like 'Johnny Got His Gun' or 'The Third of May 1808', 'Let England Shake' will remain timeless in its relevance and appeal. It's an album that speaks of the times it was written in, but has a atmosphere that is itself timeless. There isn't another album that sounds anything like it. I can't wait to see what Harvey tries her hand at next. With Beefheart for a mentor, anything is possible. An opera on the life of Emma Goldman perhaps? Whatever it is, I only hope she doesn't need to spend four years researching the next one.

No comments:

Post a Comment